At my wife Martha’s funeral, I stood alone in the rain. The sky over Mountain View Cemetery was the color of old tin, and the cold went straight through my coat as if grief had teeth. A young minister who had never met her murmured a prayer that sounded borrowed. I watched the pine box go down and listened to the ropes creak like old knees. Forty‑three years of marriage slid into the earth with a steady, indifferent grace.

I pulled out my phone the way a man reaches for a handrail in a storm. No missed calls. No messages. Out of habit I opened Instagram and found my children in a life where the rain never fell. Amber posed beside a Christmas tree at a boutique hotel in Whistler, chin lifted, a glass of champagne clipped by fairy lights. “Living my best life. Self‑care isn’t selfish.” Four hours ago. Ryan grinned in a ribbon‑cutting photo in Toronto, hard hat in one hand, another clamped by a developer whose teeth looked sponsored. Six hours ago. They were elsewhere for their mother’s last goodbye.

I stood in mud that swallowed my shoes and let the young minister talk. I said “thank you” when he finished and “yes” when he asked if I had a ride. I drove myself home along Broadway with the wipers ticking a metronome against the glass. The house was dark when I opened the door, and the quiet felt like a verdict. Martha’s slippers were by the radiator. Her mixing bowls were on the drying rack. That night I slept in the recliner because the bed looked like an accusation.

The doorbell rang at nine sharp the next morning. I had been awake since four, walking the house like a watchman, touching the back of chairs and counting pills we no longer needed. When I opened the door, both my children were framed by January—Ryan in a charcoal suit that looked like it cost more than my first pickup, Amber in pale athleisure with her hair knotted high, both clutching Tim Hortons cups and a paper sack that smelled like sesame. They stepped past me without waiting for an invitation.

“Morning, Dad,” Ryan said. His cologne took up space the way certain men do, pressing into corners and leaving no room for air.

“We brought breakfast,” Amber added, setting a large coffee in my usual spot and smiling the kind of smile that belongs in a product post. “Double‑double. Just how you like it.”

It was a small kindness, and it slid through my stomach like a stone.

They sat at my kitchen table—Martha’s table—where she used to roll cinnamon dough into spirals and leave the counter dusted with flour that caught the morning sun. Amber scrolled her phone. Ryan cleared his throat and folded his hands the way people do when they’ve rehearsed.

“Listen, Dad,” he began. “About yesterday. About the funeral. I am so, so sorry. I was stuck. It was the closing on the Yonge Street development—three years of work. Forty million. I had to be there. I’m the principal developer. I couldn’t just walk away. Mom would have understood.”

He had Martha’s green eyes, but they were polished to a professional shine, and there was no warmth in them. I remembered his first Lego tower collapsing in frustration on this floor. Martha had taught him to try again.

Amber finally looked up. “And my event was huge. A major wellness brand. Contractual deliverables, Dad. If I cancel, I get sued. It’s… complicated. It’s my work.”

I let the silence do the arithmetic. They sipped coffee. Somewhere a neighbor’s dog barked. The clock, which Martha wound every Sunday, clicked toward the half hour.

“We sent flowers,” Ryan offered. “Very tasteful.”

“I saw,” I said.

“Dad, we need to talk,” he continued, sympathy shutting off like a light. “We need to be practical.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean we need to settle the estate for everyone’s good.” He stood, fetched his leather briefcase from the hall, and snapped it open, the sound sharp in the quiet like a doorstrike. A thick folder slid across to me. “Mom died intestate,” he said with a gravitas meant for boardrooms. “No will. BC law is clear: there’s a preferential share, and then the rest is divided among the children.”

Amber leaned forward like she was chiming in on a podcast. “The house, Dad. This house is worth one point eight, maybe two—maybe more in this market. That’s a lot of equity sitting here.”

Ryan nodded. “Exactly. And you don’t need a big place anymore. Stairs. Yard. You’re sixty‑seven. A condo makes sense. We’ve already pulled a few listings.” He fanned a small deck of printouts. One‑bedrooms in New Westminster. Clean. Bright. A balcony if you squinted.

“We’ve spoken to a realtor,” he said. “She can list next week. Close by February. You walk away with your piece, buy something easy, and you’re comfortable.”

“And your pieces?” I asked.

He smiled, the kind of smile you practice in front of a mirror. “Amber and I would split the remainder. It’s only fair. We’re her children, too.”

“Fair,” I said, a word that tasted like metal.

“Dad, please.” Amber laid a manicured hand on mine. “Don’t make this hard. We’re all grieving, but we need to be smart. The market is hot. If we wait—”

“This is where your mother baked birthday cakes,” I said, not recognizing the voice until I felt the ache push up my throat. “Where we opened presents on Christmas mornings. Where I taught you to wobble a bike down the driveway while she ran behind with a dish towel.”

“Exactly,” Ryan said, patient and patronizing. “Memories. But you can’t live in memories. Reality is this is a two point three million dollar asset being wasted.”

Two point three. He had already had it appraised.

“I need time,” I said.

“You don’t,” Ryan answered, losing the adult and finding the boy who couldn’t stand to be told no. “Sign the listing agreement. You’re grieving. You’re not thinking clearly. Let us handle this.”

I stood. My knees argued. Firehouse injuries accumulate like parking tickets, small and constant. But under the ache rose something clean and cold, a ladder man’s clarity when the smoke turns black. “I want you to leave.”

“Dad, don’t be stupid,” Ryan hissed. “This house is half ours. We have a legal right.”

“Get out of my house,” I said.

“You’re going to regret this,” Amber snapped, her voice sharp with entitlement. “We’re trying to help you.”

I opened the door. January air rushed in, smelling like wet cedar and city exhaust. They left, but Ryan was already on his phone before his shoes hit the walkway.

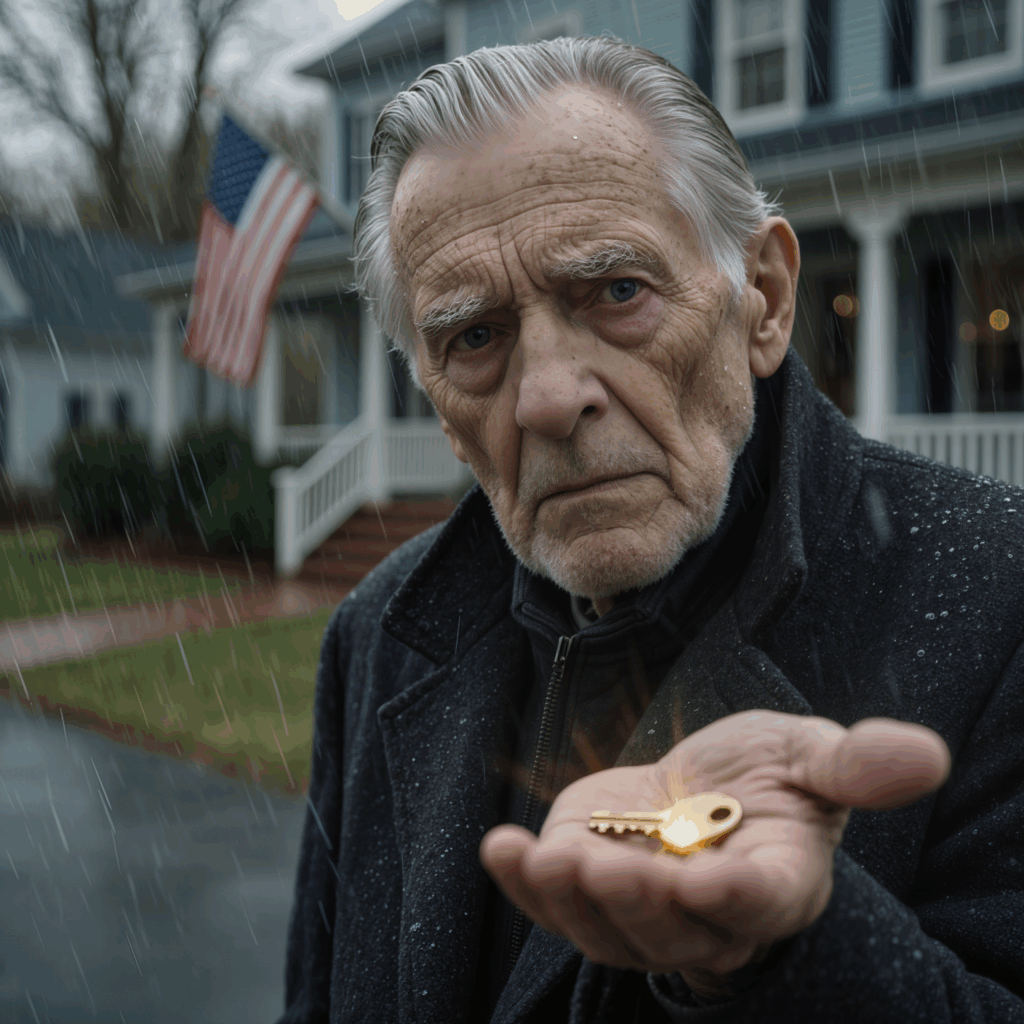

When the door closed, the quiet came back, heavier now, like a wet coat. I stood with my forehead against the wood until a thought surfaced: the key. Martha’s shaking hands in the hospital two weeks earlier, warm and papery in mine as she pressed a small brass key into my palm.

“When I’m gone,” she had whispered, “go to the bank. Box three‑one‑seven. Don’t tell them. Don’t tell anyone. Just you.”

Grief pulls time into odd shapes. It felt like ten minutes and ten years between then and now. I grabbed my coat and drove to the Royal Bank on Main, the one where the tellers knew Martha by first name and asked about her roses. The manager, Patricia, who’d known us longer than most of our neighbors, escorted me to the cool inhalation of the vault and left me at a small metal table with a long, narrow box.

Inside sat a brown envelope and a USB drive the color of gunmetal. My name was on the envelope in Martha’s cursive that had curled around a thousand grocery lists and birthday cards. I opened it and found a letter, several pages, and a document with a title that made the back of my neck go hot.

TRANSFER OF LAND TITLE — REGISTERED OWNER: WALTER JAMES MORRISON.

The date was three months earlier. Before the last hospital stay. Before Martha’s breath grew thin as paper.

The letter began, My dearest Walter, and grief buckled my knees and sat me down.

If you are reading this, then I am gone. I am so, so sorry. I am sorry that I kept secrets from you. I am sorry that our children have become who they are. Most of all, I am sorry that you are alone now. But you are not defenseless. I made sure of that.

She told me what I already knew and what I had refused to say aloud—that Ryan had borrowed one hundred eighty thousand dollars five years ago to “bridge” an opportunity and had never paid it back. That Amber had taken ninety‑five thousand to launch a lifestyle brand that lasted as long as a weather front and had apologized only to her followers for “pivoting.” Martha had kept the ledgers in her head and the receipts in a neat envelope in the bottom drawer, and every time she thought to tell me she chose peace and called it love.

When the doctor said six months, maybe less, she wrote, I knew what would happen. They would descend on you. They would take the house if they could. I could not allow it. So I transferred the title into your name alone. It was my inheritance from my parents, do you remember? Sharon says that matters. The deed is good. It is yours. But there is something else you need to see. It is on the USB drive. I recorded it while you were at physio. I am sorry. You need to know the truth.

I slid the drive into my phone with an adapter Martha always teased me about carrying and opened the only file, a video dated November ninth. The bedroom filled the frame, familiar and austere: Martha’s chair near the window, the quilt her mother had stitched, shadows from the cedar outside moving like slow water across the wall. Martha looked small in her robe, her head wrapped in that blue scarf she liked because it made her eyes pop. She shifted, winced, breathed.

Ryan entered without knocking. “Mom, we need to talk.” The voice was impatient, clipped.

“About what, sweetheart?” Martha asked, her voice a thread pulled from a spool.

“About Dad. About the house. About the future.” He set papers on her lap. “I need you to sign something.”

“What is this?”

“A transfer of beneficial interest. We put the house in a trust. Amber and I are trustees. We’ll manage the asset for Dad. He’ll have life interest. He can live there until—until it’s time. This protects everyone.”

Martha lifted the top page with slow fingers. “This says the house goes to you and Amber, not to your father.”

“Eventually,” Ryan said, a little too quickly. “But he gets to live there. We’re just protecting the value.”

“No,” Martha said. It was soft but it filled the room.

“Mom, don’t be difficult. You’re sick. You’re not thinking clearly. This is what’s best. Trust me, I do this for a living.”

“I said no.”

Silence expanded like an airbag. When Ryan spoke again, something cold had moved in. “Fine. Then we do this the hard way. When you die, there’s no will. House goes to probate. Amber and I will fight Dad for our share. It’ll take years. Tens of thousands in legal fees. Is that what you want? You want him to spend his last years fighting us in court? We’ll claim he manipulated you. Diminished capacity. We’ll make him look like a fool.”

Martha, my quiet woman who once stitched a squirrel’s tail back on a toy with such patience the child stopped crying mid‑sob, raised her voice. “Get out.”

“What?”

“Get out of my room. Get out of my house.”

“Mom—”

“Out,” she screamed, and the power of it rattled me in the vault. Footsteps. The door. The soft, long sound of Martha’s breath coming back to her in hiccups as she cried.

Then she looked straight into the lens and spoke to me across time. Walter, I am so sorry you had to see this. But now you know. The children we raised are gone. These people are strangers. Do not give them anything. Do not give them mercy they would never show you. I love you. Be strong.

The video ended. I stared at the black screen until I could hear my heart over the vault’s fan. When Patricia knocked and asked if I was all right, I said yes and surprised us both by meaning it. There is a kind of relief you only get when the truth stops hiding.

I drove home with the document and the letter buckled in like passengers. I called the lawyer whose name was on the title transfer—Sharon Chen. Her voice was clear as clean glass. She could see me at three if I brought the paperwork.

Her office sat on the fifth floor of a brick building that had seen better decades and decided to keep going anyway. Sharon wore a navy suit and a pragmatist’s expression. She read quickly, then slower, then nodded once.

“Your wife was a very smart woman,” she said. “She transferred the property as a sole‑owned asset from her inheritance. We have the doctor’s capacity assessment. The witnessing is clean. The Land Title Office stamps are in order. It’s bulletproof.”

“They’ll fight,” I said.

“They can try,” Sharon replied. “But if they do, we file this.” She tapped the USB drive. “Judges have little patience for adult children who threaten dying parents.”

“Is there anything else?” I asked, and even as I asked it I felt the letter heavy in my coat like a second heart.

“As a matter of fact,” she said, sliding another file across the desk. “Your wife set up an education trust for the grandchildren. Two hundred thousand to start. It vests directly to the kids at eighteen. No parental access. She was very clear.”

I breathed for what felt like the first time in days. “She wanted something to survive us,” I said.

Sharon nodded. “She made sure of it.”

Three days later a courier slid a thick envelope through my mail slot. Ryan’s lawyer. They were contesting the title transfer: coercion, undue influence, diminished capacity. Sharon filed a response with the video. Forty‑eight hours after that, Ryan’s counsel withdrew “without prejudice” and suggested mediation that never materialized.

Amber called crying. “Dad, please. My landlord raised my rent. I have nowhere to go. Sponsors dried up. The algorithm changed. I need help. I’m your daughter.”

“My daughter would not have tried to take my home,” I said and hung up shaking.

At eleven one night Ryan pounded on the door, drunk enough to be brave. “You can’t do this,” he shouted at the security camera. “That house is mine.”

I called the police the way I had told a thousand people to do in a thousand kitchen talks, and when the officers arrived they were polite and efficient, and they spoke to me like a man who deserved respect. They told Ryan to leave. I changed the locks. I slept for an hour and felt like I had run a marathon when I woke.

Days had a way of both collapsing and stretching in those weeks. I learned how long a spoon looks in a cup without a second mug beside it. I learned which days the condo listings refreshed. I learned that there is an ache that lives behind your breastbone like a hidden tenant and that you can make coffee around it, read the paper around it, call old firehouse friends and talk about nothing around it until it becomes another thing a man carries.

I sold the house, not to line anyone’s pockets but because Martha was right in more ways than one. Grief has square footage. This place had too much of it. We’d bought the house when Ryan was six and the city smelled like sawdust and wet leaves, and we’d stayed through good jobs and bad engagements and knees that would never again climb ladders like they used to. It went for two point four. I bought a small, bright condo in Kitsilano with a view of the ocean if you leaned a certain way on the balcony. Everything on one floor. A kitchen I could clean in ten minutes. I took the rest and added five hundred thousand to Martha’s trust and worked with Sharon to weld shut any seam Ryan and Amber might find.

The grandchildren—Ryan’s two, Amber’s girl—visited on Sundays twice a month. Ryan’s wife had seen the video and her face changed in a way that made it clear something in their house had rearranged itself. She was the one who insisted on visits. Amber’s ex dropped off her daughter with a tight smile and the casual movements of a man who had learned how to keep a fight in his pocket.

I kept cookies in a tin and showed them how to feed coins into the little mechanical bank on the bookshelf so the cast‑iron hand swallowed change. We walked to the aquarium and stood quiet in the blue light of the jellyfish room where even loud children accept a stranger’s hush. For ninety minutes at a time the past loosened its grip and I was simply the man who knew where the sea otters liked to sleep.

Ryan and Amber were quieter. Ryan sold the Toronto condo and moved somewhere less glossy. Amber took a job teaching yoga at a fitness studio that smelled like eucalyptus and laundry. I didn’t feel triumphant. There’s no victory in discovering you raised two people who lost the map you gave them. There’s just the work of living with it.

Winter peeled away from the city in late March, and with it some hardness in my chest. I learned the names of the neighbors in the condo building—Retired Navy, Nurse on Night Shift, Student With Cat, Couple Who Make Sourdough—and they learned mine. I went to breakfast with old firehouse friends on Wednesdays, where we told stories that were eighty percent true and laughed like the twenty percent didn’t matter. I took a woodworking class at the community center and made a cutting board with end‑grain maple that Martha would have run her palms across as if it were a miracle I’d performed just for her.

On Easter, I bought white roses and went to the cemetery. The ground was still damp, and the air had that clean brightness that makes you think of laundry on a line. I told Martha about the condo and the aquarium and how the littlest grandchild laughed like a hiccup. I told her she had been right about everything that mattered. I sat until my hips told me to stand. I stood until the wind told me to go home.

In May I received a letter from Ryan—real paper, real stamp, real handwriting that looked like his fifth‑grade teacher’s comments on a science fair project. He wanted to meet. He wanted to apologize. He wanted, he wrote, to make things right. I put the letter on the counter and walked around it for two days. Then I called Sharon and asked her to join me at the coffee shop on Broadway, because I am not a fool just because I want to be a father.

Ryan arrived ten minutes late and looked smaller than his suit. He took off his hat and held it like a schoolboy. “Dad,” he said, and the word landed like a pebble in shallow water. “I’m sorry. I was… I was scared when Mom got sick. I was scared of losing everything, and I made it worse. I don’t want to be that person. I’m in a program. I stopped drinking. I sold the fancy car. I… I want to earn back your trust.”

People don’t apologize the way you want them to. They don’t say the exact words or take the exact shape you think redemption should take. They come with pockets of truth and pockets of what they need from you. I listened. I told him I was glad he’d stopped drinking. I told him I was glad he had a job. I told him trust wasn’t a switch. He cried and didn’t try to hide it, and that felt like the truest thing in the room.

He asked about the trust for the kids, and I told him plainly that he would never, under any circumstance, have access to it. He nodded. “I figured,” he said. “I still wanted to hear you say it.” When we stood to leave, he hugged me the way men do when they aren’t sure where shoulders go. I didn’t forgive him, not like a movie. But I loosened my jaw, and the world let a little more air in.

Amber took longer. She texted short messages—Happy Birthday, Dad; Thinking of you; Can we talk sometime?—and each one felt like stepping onto a dock with a rotten board somewhere beneath my foot. We met in a park near her studio on a day when half the city had decided to believe in sun. She looked tired in a way filters can’t fix and held a paper cup with both hands.

“I messed up,” she said without preface. “I keep trying to be someone people will like and I keep ending up alone with boxes of things companies sent me for free.” She laughed, a small, sharp sound. “I’m good at teaching. I’m good in a room with ten people and no phones. I don’t know who I am outside of a post. I want to find out.”

We walked a loop and didn’t try to make it more than it was. She asked if she could bring her daughter by the condo the next weekend. I said yes. She cried a little and didn’t hide it either. Maybe there’s a point in a life where you stop hiding the parts that make you human.

Summer leaned in. The condo filled with a friend’s guitar and the smell of coffee and the slow knowledge that mornings could be good again. With Sharon’s help I wrote a will that could withstand a siege. I made a list of things to do with whatever time is left to a man who has already dodged enough fires: visit the Rockies like Martha always wanted, teach the youngest to ride a bike in the parking lot behind the community center, fix the old mantel clock that never kept time but insists on trying.

One night in July, the whole city glowed copper and pink and somebody down the block grilled something with garlic that made the air smell like a party we hadn’t been invited to but could hear. I leaned on the balcony rail and felt, for a stretch of minutes, something like happiness, and it scared me less than it used to. I told the empty room, “You were right,” and heard the kind of silence that feels like an answer.

In August, I took the grandkids to the PNE. We rode the wooden coaster that rattled my bones and made them scream like delighted sirens. We ate mini‑donuts that dusted sugar on our shirts and watched a lumberjack show where men in suspenders ran on logs like they were born on water. For an hour, we sat in a tent and listened to a fiddler play a reel so fast it felt like the tent might lift, and the youngest fell asleep on my lap with his mouth open, and I thought, This is what survives.

On the anniversary of Martha’s death—one year on a calendar that still looks wrong when I flip it—I went back to Mountain View with roses and a thermos of coffee and the letter folded small in my pocket. A breeze moved through the cedars. The city hummed beyond the fence like a polite neighbor. I told her about the summer and the coaster and how Ryan looked smaller and truer and how Amber was learning to live in rooms without mirrors and how the children were growing like weeds you don’t mind.

I told her I finally moved the box of her scarves from the hall closet into the bedroom, and then back again, because grief is messy and nobody gives you a diagram. I told her about the cutting board. I told her that the clock still wouldn’t keep time but I was getting closer. I told her that I had stopped waiting for the sound of her steps at night and had started listening instead to the swell of the ocean when I cracked the balcony door at two in the morning. I told her that I loved her and that I was living like she asked.

On my way back to the car I saw Patricia from the bank standing with a bouquet at another stone. We waved. That’s how life is: you recognize people in unexpected places and feel, for a second, part of a small, sane club.

The thing about being sixty‑seven is that people expect you to be finished with your firsts, and then, without asking permission, the world hands you a few more. First morning you wake and the first thing you feel is not crushing sadness. First lunch with your son where you talk about nothing that needs a lawyer. First time your daughter makes a joke and it lands exactly where laughter lives. First time you sit on a beach and let the tide erase your footprints and believe that impermanence can be mercy instead of theft.

Sometimes I think about the night of the video and the way Martha raised her voice, my quiet woman who rarely did. I keep it on the drive in the desk, and I don’t watch it anymore, but I keep it like a lighthouse keeps its lens: as proof that there is a way through fog if you make your light and hold it steady.

I still visit the firehouse once in a while. The kids there—because they all look like kids to me now—humor the old man and let me check the rig and tell stories about the time a raccoon got itself locked in a pantry and we all pretended not to be afraid of those hands. They listen the way people do when the stakes are simple: don’t be stupid, wear your gear, trust the person on your left.

At home, I learned to cook for one without making it a ceremony. You can eat well by yourself. You can light a candle without pretending it’s for anyone else. You can sit on a balcony and watch the night fold around the city and remember a woman who loved you enough to save your life with paper and ink and courage.

If you asked me what I learned, I would say this: love and enabling are distant cousins who sometimes borrow each other’s coats. Boundaries are not walls; they are good fences with gates you open on purpose. Money is a loud instrument that drowns out quieter songs if you let it. And forgiveness is work, not magic. Some days you can lift it. Some days you set it down and pick it up again tomorrow.

In October, Ryan invited me to a school play where his son had three lines and said them like they were the difference between daylight and dark. Afterward, Ryan shook my hand in the parking lot and didn’t try to apologize again. We stood in the exhaust breath of minivans and watched his boy run in circles with a cape a mother had made out of a curtain. “Thanks for coming,” he said. “It meant a lot to him.” It meant a lot to me, too, and we let that be enough.

In November, Amber hosted a small class called “Strong Backs, Soft Hearts,” and I went because I wanted to see the person she was when she wasn’t looking in a camera. She taught with a calm, firm voice, and when an older woman in the back began to cry during savasana, Amber sat beside her and placed a hand on her shoulder without speaking. After class, she hugged me and pressed her face into my coat and said, “I’m trying, Dad.” I told her I could see that.

I keep Martha’s letter in a drawer, and once a month I unfold it and read the first paragraph and the last and put it away again. I don’t need the middle anymore. I know it by heart. I keep the land title in the same folder, not because I need to wave it at anyone but because I like the clarity of its font: REGISTERED OWNER: WALTER JAMES MORRISON. I keep a list on the fridge in Martha’s handwriting that says, in this order: Milk, Eggs, Butter, Call Walter when you pick up the dry cleaning, and I have never thrown it away because some things anchor you to a life you can still recognize.

When the rain comes—and in Vancouver it always does—I let it. I sit by the window with a book or nothing and watch the street become a moving mirror. I think about a woman in a blue scarf who stared down a storm and saved a house and a man and a future she would not live to see. I think about a morning when my children tried to claim my home like a prize and how, because of her, they couldn’t. I think about the grandchildren whose names I say out loud when I am alone because saying names makes people real and keeps the air honest.

I am not the man I was when the pine box lowered, and I am not the man my children thought I was when they showed up with coffee and a plan. I am the man who stands on a small balcony over a city that keeps its promises and sometimes even keeps its people, and I am the man who lays roses on a grave and says things he means, and I am the man who answers the door when Sunday knocks and lets three kids track rain across his floor because joy is messy and that’s how you know it’s here.

Martha’s voice lives in the corners of rooms and the backs of drawers and the way I check the stove twice. It says, “You’re free now, Walter. Live.” I do. Some days it looks like a walk to the market for oranges that smell like Christmas. Some days it looks like a nap in a chair that fits my body the way our marriage fit my life: worn in, sturdy, forgiving. Some days it looks like saying no and meaning it without apology. Some days it looks like saying yes to a play or a class or a laugh that feels earned.

On a morning that looks a lot like the morning after the funeral except that it doesn’t hurt in all the same ways, I look out at the water and think, This is enough. Not because I’ve given up on more, but because I’ve stopped measuring my life by what other people think it should hold. I have my name on a deed, a letter in a drawer, a clock that tries, a cutting board that gleams, three grandchildren who love mini‑donuts, a son and a daughter learning how to be people I can know, and a wife who is everywhere I look whether or not you can see her.

This is how the story ends, and, like rain on cedar, it leaves a clean smell behind. I stand in a kitchen made for one and pour coffee for a man who finally understands that protecting what you love is a way of loving it—and that there is no shame in building a fortress when the wind comes.