What would you do if your own child tried to take everything you and your husband built across thirty-seven years of marriage? If a judge asked whether you were fit to handle your own life while your son sat at counsel table looking anywhere but at you?

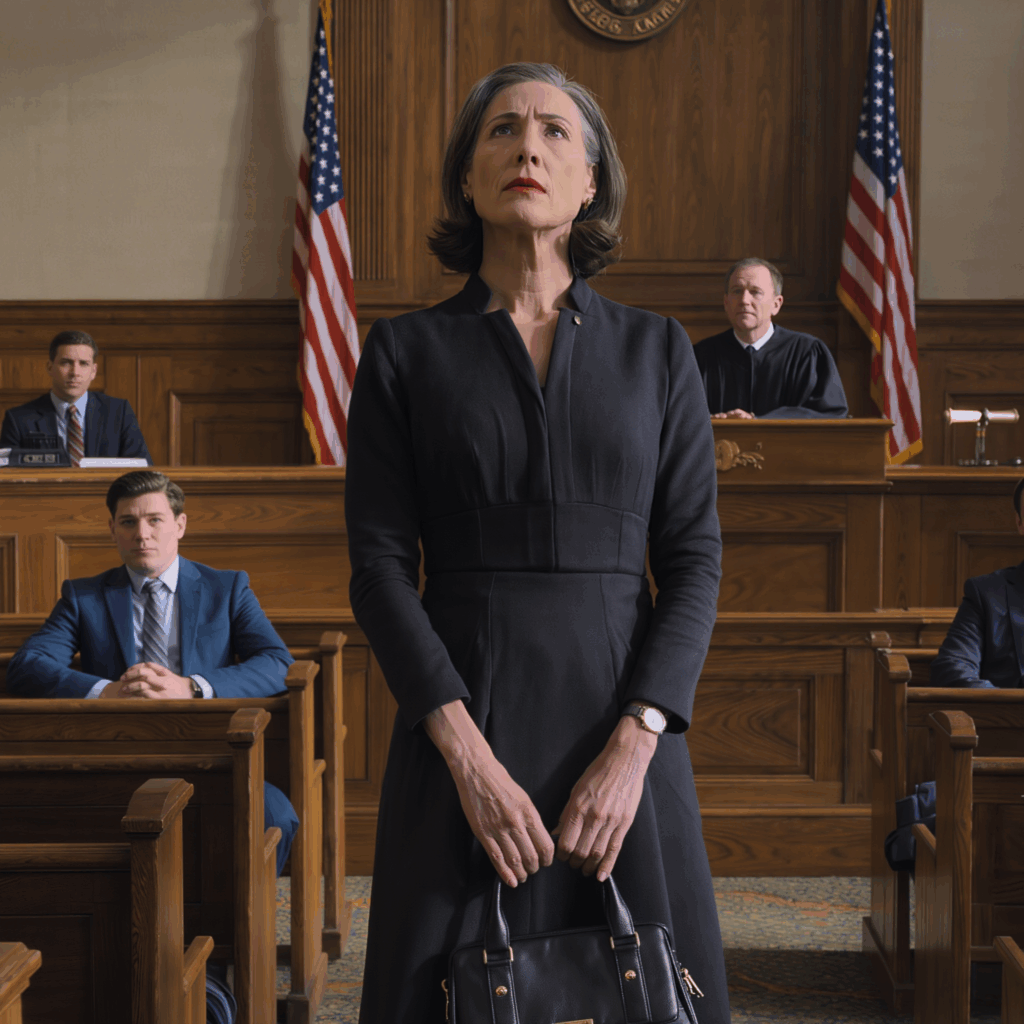

The courtroom smelled like old books and lemon floor polish. The benches were polished from a hundred other stories before mine, each one leaving a shine where people had clutched wood and hope. The air hummed with whispers and the nervous tapping of someone’s pen. I sat in the front row beside my attorney, a patient woman with sensible heels and eyes that could steady a ship. I kept my purse on my lap like a life raft.

Across the aisle sat my son. Eli. My boy who used to fall asleep on my chest with his hair sticking to his forehead. He wore a sky‑blue suit that fit like it had been cut for someone meaner. His jaw worked the way his father’s did when he was holding back anger. He didn’t look at me. Not once.

His lawyer did plenty of looking. Slicked‑back hair, a watch with a face big enough to read from the back row, and the kind of grin you practice in mirrors. Every time he turned that grin toward the judge, I pictured a cartoon villain twirling a mustache. If he’d started cackling, no one would’ve been surprised.

The case, in its bones, was simple: my husband, Frank, had died last year. His will left everything to me, as it had every year since we first drafted it at a plastic desk in a strip‑mall office in Dayton, Ohio, back when Eli was eight and ran laps around the chairs while we signed. Frank updated that will, then later built a revocable trust to make things easy. He kept notes, letters, and receipts because Frank believed paper told the truth. He’d told me, more than once, “If anything happens, Nora, you keep the house, the shop, the savings. You were the one holding the line with me.” I used to tell him not to talk like that. Then cancer made us speak in full sentences.

Eli didn’t like the part where his father’s wishes didn’t involve him immediately. He called it “unfair.” He called it “not how families do it.” He called me “distracted” and “wasteful” and “stuck in the past,” which was new. He had a business idea—there’s always a business idea—an app that would apparently save America from bad coffee. He needed capital. He said Dad would’ve wanted him to have a shot.

Frank would’ve wanted him to work.

“Case number 23‑P‑1897,” the bailiff called, and the judge swept her glasses down to her nose and peered over them. The seal on the wall looked like it had watched a thousand regrets.

Eli’s lawyer stood with a flourish. He spoke about me like I was a headline. “Petitioner requests control of the estate to prevent ongoing waste,” he said, as if the word itself had a taste. He used phrases that sounded important—mismanagement, dissipation of assets, undue hardship—and every time he said one, another spectator wrote it down like they were collecting souvenirs.

I wanted to laugh. Me, who still takes jars back to the store for the deposit. Me, who clipped coupons when Frank’s hardware shop had three customers in a whole afternoon while the big boxes ate the neighborhood. Me, who mended winter coats and salted driveways and learned to stretch a roast into three meals because we had a boy growing fast and a mortgage growing faster.

When they swore in Eli, his hands shook a little. He pointed at me and said, “She only knows how to waste what she didn’t earn.” The sentence dropped in the room like a glass. My name is Nora, and I have learned that you can love somebody and still feel anger rise like heat behind your eyes. I kept my spine straight. My attorney touched my sleeve. Breathe, her finger said. Breathe.

If you’re waiting for me to tell you I shouted back, I didn’t. The truth is quieter. It builds like a storm the meteorologists keep saying will miss you and then finally comes in sideways.

“Mrs. Whitaker,” the judge said at last, turning to me. “Do you have anything to say?”

“I do,” I said, and my voice surprised me by not trembling. “I think we might all benefit from watching a short video.”

The attorney beside me didn’t blink. She slid a flash drive from a labeled envelope—Frank’s handwriting sharp and neat: FOR EMERGENCIES ONLY—and handed it to the bailiff, who handed it to the clerk, who made a small production of seating it into the laptop at the side of the bench. The monitor on the rolling cart flickered. Static. Then the sharp, plain light of our old study.

And there was Frank.

He’d recorded it two years ago, after one of those late‑night talks when sore throats and whispers ring louder than a radio. He sat at his desk with the ceramic owl I hated on the shelf behind him and the good lamp casting a soft circle on his face. He looked tired. He looked like himself.

“If you’re watching this,” he said, clearing his throat, “it means something’s not easy.” He smiled, small. “Nora, if you’re there, I want you to breathe.” He leaned forward. “Eli, son, if it’s you, you know I love you. You also know how I feel about work and about promises. I built that shop with your mother. I kept it open because she was there at midnight counting washers with me. I left everything to her because she’s the reason our house was a home. If you love her like I asked you to love her, you’ll let her live in peace. If you’re thinking about using lawyers to get your way, son, don’t. Grow something that’s yours.” He looked down, then back up into the lens. “This is my call.”

The room held its breath.

Eli looked down at his shoes as if they’d tell him something different. His lawyer coughed, then didn’t say anything at all.

The judge’s glasses glinted. She folded her hands. “I think that settles the matter,” she said after a beat, and the sound of the gavel was almost gentle.

You’d think that would be the end of it. Court adjourned; the widow goes home, makes tea, and stares at the wall until the sun shifts and the shadow reaches the lamp. But grief doesn’t line up when the clerk calls case numbers, and family doesn’t end because a judge says so.

I drove home with the radio off. The Whitaker house sits on a street that caught its name from the big maple that splits the afternoon light—in autumn, it looks like the sky caught fire. The driveway holds the oil‑dark ghosts of old trucks and the chalk hopscotch squares of neighbors’ kids who sometimes cut across our yard because Frank always buzzed the mower to make the grass look like a baseball diamond. I parked, walked up the steps, and unlocked my door.

It felt lighter inside, like a room exhaling. I poured a glass of wine, set Frank’s old Motown playlist on low, and danced in the kitchen in my socks. The floor is linoleum—yellowed, cracked near the vent—and it squeaked each time I turned. I laughed alone. I cried alone. I did both at the same time; women are good at that.

But the story of what happened to me isn’t just a courtroom clip you can upload and share. It’s the long road that led there and the longer road after. It’s the dinners where Eli came late and left early, shaking app‑ideas out of his sleeves like confetti. It’s the mornings when Frank’s breath slowed and I timed pills to the second and sang along to the radio even when the only sound in our house was the hum of a machine. It’s the envelope in the nightstand with a letter that says, in Frank’s block print, Because you always made our house a home.

So I’ll tell you the rest. Because we don’t heal on verdicts alone.

The year before Frank died, he closed the shop on Wednesday afternoons so we could drive to Hawthorne Lake and sit on a bench with coffee like the old people we had finally become. Eli rarely came. He said lakes were for Instagram hikers and the city was where real life lived, and he was probably right for the version of life he wanted. Frank would say, “That boy’s going to be a problem and a miracle, probably in that order,” and then he’d pass me his blueberry muffin and I’d pretend not to take the bigger half.

We tried to raise Eli the way you raise a tomato plant against a stake—firm but with room to lean. He was on travel baseball one summer and I kept a cooler in the trunk. He wanted the expensive bat the other boys had, the one the coaches whispered about like it was a magic wand. We bought him something sturdy instead. He hit anyway. When he struck out, he took off his helmet and looked at the dirt; when he hit a double, his smile split him open. He was a kind kid. He helped Mrs. Dawson carry her groceries, and he cried when we ran over a rabbit’s nest while mowing.

The world got loud for him in high school. Loud friends. Loud choices. Loud ideas that sounded like rockets on the way up and falling safes on the way down. College gave him bigger rooms to be loud in. He switched majors like he switched sneakers, always chasing the newest pair. After graduation, he said he was building something that would change everything, and we clapped because belief is a kind of love you offer even when you’re not sure.

The shop stayed steady—nuts, bolts, paint, keys—and the town stayed smaller than it thought it was. Frank taught Eli the books one spring when he came home for three weeks, swearing he wanted to learn the business. By June of that year, he wasn’t at the counter anymore. He said the customers were rude and the register was a coffin. He left in a rush for Columbus, then for Austin, then for a co‑working space in a warehouse with exposed brick and cold brew. Every time he called, he sounded farther away.

The cancer came in like a gray day. The doctor said the word and the world rearranged itself around it. We did the treatments and the lists—insurance, wills, the small discipline of making sure the car registration was renewed because wheels keep turning, disease or not. Frank got thinner. He refused to leave the shop until the last month. When the hospice nurse asked what he wanted near him, he said, “Nora. The radio. A pencil.” He died on a Saturday morning in late October when the first frost had just touched the pumpkin vines. Eli flew home that night and stood in the doorway like a storm you can smell before it hits.

We buried Frank on a Wednesday. The town came in work boots and church shoes. The men from the VFW folded a flag because Frank had fixed a thousand lawnmowers for half price for veterans who couldn’t afford the full. As the minister spoke, Eli looked at the sky and at his shoes and then at me, and in his face I saw a boy whose kite had come down hard in a tree.

Grief makes accountants of us. You count what you had and what you didn’t say and the hours you slept and the ones you lay blinking at the ceiling and the ways people show up. The day after the funeral, there were casseroles and flower cards and a stack of envelopes with checks because people don’t always know what to do with sorrow except try to pay a piece of it down.

Two days later, Eli started asking questions. How much is in the shop account. What’s the house worth. Will you keep the store. Do you need all that space. Words came from him that sounded like advice but sat in my ear like demands. I told him his father had made it simple—everything to me, then later to him when I was gone. He frowned like a man studying a map that forgot the road he wanted.

“You don’t need all of it,” he said. “It’s not like you’re going to start traveling the world. I could double it now. Triple.”

“I need the house,” I said. “I need the shop long enough to sell it right or to pass it to someone who’ll love it. And I need quiet.”

The quiet didn’t last.

By spring, Eli had a new plan with a deck and a logo and friends who wore black T‑shirts and said things like burn rate and runway as if we were all standing at the end of an airport tarmac. He wanted seed money. He wanted to restructure the trust. He wanted me to loan to him “at below market rates because family,” with his own repayment schedule, which looked a lot like the horizon—pretty and always out there. When I said no, he told me I was living small. When I didn’t pick up the second time he called back‑to‑back, he left a voice mail I couldn’t listen to in one pass because the words stung. A month later, I received the first letter from the attorney. Then a second. By summer, there was a case.

If you’re asking where I made mistakes, I can name them: I didn’t hold the line as hard when he was twenty‑two and sleeping on our couch “for a week” that became four months. I gave him the old Corolla when he asked, even though Frank said Eli needed to come up with half. I told myself love meant softness. I confused forgiveness with erasing what happened. I confused patience with paying interest on someone else’s decisions.

But I also did this right: I stayed when it was ugly; I worked when we were tired; I kept the lights on. I put my hand on Frank’s back when he coughed and told him I had him even when I didn’t know if I had me. I read the wills. I kept the papers. I stopped the pot from boiling over when I forgot I’d put it on.

The day of court, I wore Frank’s flannel shirt under my jacket because grief makes children of us, and I wanted him with me while men in suits spoke about my life like it was a business plan.

When the gavel came down and the judge’s decision sat on the record, I walked out into a slice of Ohio sky so blue it almost hurt. Eli hurried past, his eyes shiny with anger, his lawyer trailing like a kite whose wind had died. He didn’t look at me—again. The hallway smelled like paper. Someone’s heels clicked like a metronome. I stood by the stairwell until the fluorescent lights stopped buzzing in my ears.

He didn’t call that night. He called the next day. “You made me look like an idiot,” he said.

“Eli,” I said, and if my voice was soft, it was soft like a rope burns soft just before it snaps. “Your father spoke for himself.”

“You made him do that,” he said.

“Your father never did anything he didn’t decide to do,” I said, and I could hear Frank laugh somewhere in the way the sentence ended. “You know that.”

Silence on the line. He exhaled. “I can’t believe you’d rather keep me small than help me build something.”

“You are not small,” I said. “You are also not entitled to skip the part where you build.”

The line clicked dead.

I tell you the hard parts because love is made of them, too. The next week he left three short messages. He didn’t apologize. He asked to “loop back” on numbers, like I was a colleague instead of his mother. I didn’t return the calls. Two days later, he sent an email with a new plan that looked like the old plan, only with bolder arrows. He said he’d been offered a spot in an accelerator. He said he was “so close.” I closed the laptop and went outside to pull dandelions because you handle what you can hold.

A month after the verdict, I put the shop up for sale. I didn’t list it with a big firm. I put a handwritten sign in the window and told the first three customers who came in that morning that I was looking for someone who would keep the place smelling like sawdust and coffee. By the time I swept at closing, the town knew. The next afternoon, a woman named Lydia pushed open the door and looked around like someone walking into a church. She was fifty, with a braid thick as a rope and hands that had seen weather. “My granddad ran Willis Hardware down in Wilmington,” she said. “I’ve got receipts from ’54 that still smell like the counter.” She told me about her son who was good at locks and her daughter who could find any paint color by memory. She told me she believed there should always be a place in a town where you can buy one screw and not a whole blister pack. I cried behind the register and then pretended it was dust.

Two months later, Lydia bought the shop for a fair price. We stood in the empty aisle between Garden and Fasteners while the light angling through the glass made the dust look like confetti, and I handed her the keys. “Keep the coffee,” I said. “People need to smell it when they come in.”

“I will,” she said. “I’ll keep the counter bell, too.”

At home, I went through the drawers like a careful archaeologist. In the back of Frank’s desk I found three postcards he never mailed to Eli, each with a single line: Proud of you. Keep going. You’re loved. I sat there a long time with those three sentences in my hand and then I tucked them back where I found them because some things are for fathers and sons across distances I can’t cross for them.

In August, Eli showed up. I saw his shadow pass across the glass in the door and felt my heart do the old leap. When I opened it, he stood there with that same sky‑blue suit jacket draped over his arm in a summer heat thick enough to wring out of a shirt. He looked older, which is something to say about a boy you once held in the palm of your hand.

“Can we talk?” he asked.

“We can,” I said, and moved aside.

He sat at the kitchen table—the same one where we’d done homework and taxes and worried—and scrubbed his hands over his face like he was trying to erase the last few months. He didn’t touch the glass of water I set down.

“I got kicked out of the accelerator,” he said finally. “They said the product wasn’t ready. They said the market was moving someplace else.” He huffed a laugh that didn’t contain any joy. “They said a lot of things.”

“I’m sorry,” I said.

He nodded like he’d expected me to say something else, then shook his head. “I said terrible things to you,” he said—not an apology yet, but like a man feeling around for a door in the dark.

“You did,” I said. “So did I, in my head.”

He went still, the way he used to when I told him I knew he’d taken a cookie and he tried to make his body a lie. “I miss Dad,” he said, so quietly I nearly missed it.

“Me too,” I said, and in the space between the words we both breathed.

We didn’t fix it in an afternoon. If you came looking for a scene where a son drops to his knees and begs forgiveness while a choir sings three hymns, you won’t find it here. We began again the long way—in small, repetitive acts that look boring from the outside. He came by on Thursdays to help carry boxes from the basement. I packed a crate of old Christmas lights he once tangled when he was ten and wrote ELEPHANT KNOTS in Sharpie on the lid and he laughed. He took the mower out and cut the backyard in stripes. He didn’t ask for money.

In September, we drove out to Hawthorne Lake. I brought the old thermos, and he brought blueberry muffins from the bakery Frank liked. We sat on the bench, and for a long time we didn’t talk. The water looked like glass you could walk out onto without sinking. A boy tossed a rock, and the circles widened and widened until they touched our feet. Eli said, “I keep thinking if I just had one more chance, I could get it right.”

“That’s what everyone thinks,” I said. “Some of us get it. Some of us don’t. What we always get is a next morning.”

“I thought you didn’t believe in second chances,” he said, not accusing but curious, like a scientist poking at a petri dish.

“I believe in consequences,” I said. “And I believe people can grow. Growth doesn’t cancel consequences. They live together.”

He nodded. “That’s inconvenient.”

“Very,” I said, and we watched a mallard cut a clean V in the water like somebody’d drawn it with a ruler.

He took a job the next week at a small contractor’s office downtown—project coordinator, paperwork, budgets, the math of getting materials from one place to another without losing your mind. It wasn’t flashy. It didn’t have a logo that made your eyes roll. It had coworkers who brought donuts and an owner who’d run his crew for thirty years without a single lawsuit, which in this world felt like a miracle.

He stopped wearing the sky‑blue suit.

On a Sunday evening in October, he knocked on my door holding a cardboard box. “Found something of Dad’s,” he said. He set the box down and pulled out a Mason jar half‑full of old nuts and bolts and two Polaroids from 1986—the year the shop opened—Frank standing in front of the sign he’d painted himself, the letters slightly uneven like teeth.

“Keep them,” I said.

He traced the letter F with his thumb. “He always believed in me,” he said.

“So do I,” I said. “That’s why I say no.”

He laughed and then didn’t. “You think I can do small for a while?”

“I think you can do honest,” I said. “Small is just the word we use when we mean honest doesn’t impress anyone at a party.”

He stood there a long time, and I watched the boy and the man take turns wearing his face.

By Thanksgiving, we had made a truce with shape and rules. He came over at noon with pies—store‑bought, but in a tin he’d warmed so the crust would fool you a little. I made turkey with too much butter. We set a plate at the end of the table for Frank and ate at the pace people do when they’ve cried that day and it made them hungrier. After dishes, Eli did something he hasn’t done since he was seventeen—he asked if he could help put up the Christmas lights.

We stood in the driveway untangling wires while the cold bit the tips of our fingers. Eli laughed when he found the strand labeled ELEPHANT KNOTS. He looked up and pointed at the roofline. “Remember when Dad pretended to be Clark Griswold and almost slid into the gutter?”

“He wasn’t pretending,” I said, and we both laughed hard enough to bend at the waist.

That night, when the porch glowed gold and the maple out front looked like a giant was shaking a jar of stars over it, Eli hugged me. Not perfunctory. Not quick. He wrapped his arms around me the way he did when baseballs were hard and homework was harder. When he pulled back, his eyes were wet.

“I’m sorry,” he said.

“I know,” I said, and let myself believe him.

There are people who will tell you forgiveness is a switch. Flip it, and it’s done. I have learned it’s a dimmer. You turn it a little every day until the edges of the room don’t bite so sharp. Some evenings, the light is brighter. Some mornings, it’s low again. You keep your hand on it. You keep choosing. Sometimes you choose to keep distance. Sometimes you choose to bring soup. You do both because you’re a person and not a headline.

In December, I went to the shop under its new name—Lydia had hung a fresh sign with painted ivy curling around the W. She kept Frank’s bell on the counter, just like she promised. When I pushed the door open, it rang the same note it always had. The place smelled like cedar and coffee. Lydia had moved paint swatches to the front, and her daughter had made a display of hooks and handles that looked like jewelry for a practical person. There was a photo near the register: Frank in ’86, hair thick and mustache braver than the decade, grinning at something just out of frame. Lydia had tucked a little handwritten label under it: FIRST DAY. I touched the glass.

“Want a cup?” she asked me, lifting the pot.

“Yes,” I said. “Just like always.”

We stood in companionable quiet while a man came in for a single bolt and a teenaged girl asked if they had a key blank in the shape of a sunflower. When I left, Lydia handed me a tiny paper bag with two screws in it. “For emergencies,” she said, winking. I laughed all the way to the car.

On Christmas Eve, Eli and I drove through town to look at lights, like we did when he was little and I swore each year I’d get new ones because ours flickered. We drank cocoa from gas‑station cups and played that radio station that only exists in December. At a red light near the library, he said, “I’m thinking about taking night classes. Project management. It’s boring.”

“It’s steady,” I said. “Boring is a gift.”

He grinned. “You would say that.”

“I would.”

We turned down our street, and the maple threw light in fat coins across the pavement. At the house, we sat a minute in the idling car. He cleared his throat. “Dad would have liked to see me do something that wasn’t about me,” he said.

“Dad did,” I said. “He saw you carry Mrs. Dawson’s groceries. He saw you hand a hamburger to the man under the overpass without telling anybody you did it.”

He leaned his forehead on the steering wheel. “I don’t deserve how much you believe in me.”

“Very few of us do,” I said. “We try anyway.”

We went inside. We put stockings on the mantel. I set out the plate of cookies he always pretended Santa ate even when he was taller than me. We watched an old movie where people speak in fast sentences and kiss like they’ve been speedwalking toward it for an hour. He fell asleep on the couch, and for one long, soft stretch of time, my house held both the past and the future in the same room.

On New Year’s Day, I took the flash drive from the folder and put it in a fireproof box Frank had labeled IMPORTANT. I wrote on a sticky note in thick black letters: Seen. Heard. Saved. Then I made a second note that said: Use only if the world forgets again who we were.

The world will forget. That’s what it does. But we can remind it. We can tell the long version. We can say a woman stood up in court while her son said words that splintered her. We can say she breathed and didn’t break. We can say a video played and, more than that, a life did: a shop counter, a blue thermos, a lake bench, a Christmas strand labeled ELEPHANT KNOTS. We can say love is the hardest job some days and the only one worth clocking in for.

Spring came back like it always does, like a promise kept. The maple let down its green. The shop’s door rang its bell over and over as people came in needing screws and conversation. Eli sent me a photo on a Thursday of a spreadsheet with a caption: I balanced it. I sent back a photo of the pie on my counter with the caption: I did, too.

We are not a miracle. We are a family. We are a story where a son had to learn to work and a mother had to learn to say no without apology and a father kept telling the truth from beyond a screen. We are a small house on a street with a tree that keeps teaching the neighborhood about seasons, and we are the people who live in it, and we are okay.

If you’re a woman reading this in a kitchen with a floor you’ve mopped a thousand times and a life you’ve built out of lists and love, I want to tell you something my husband wrote me on a scrap of paper and tucked into the pocket of my coat the winter he got sick: You have always been the home. You are allowed to keep it.

I am keeping mine.

And so, when people ask me about the day in court, I say the judge’s glasses caught the light and my son said something he can’t unsay and my dead husband reminded the room who we were. I say I went home and danced in my socks on linoleum and laughed at how bad I am at twirling. I say my knees hurt the next morning and I made coffee anyway and the sun cut through the kitchen window like an apology for all the gray. I say we kept going.

That is the twist I promised you at the beginning, the one no one guesses because it doesn’t look like fireworks. It looks like steadiness. It looks like a mother drawing a line and a son stepping back from it, stunned and then humbled. It looks like a bell ringing when a door opens and a life being lived on purpose, one small, glorious, ordinary day after another.

And if you were to stand outside my house on a Tuesday evening in June, you might hear music through the screen door and a laugh that sounds like it had to fight its way out and a voice—my voice—saying, “Dinner’s ready,” and another voice—my son’s—saying, “Be right there.” That isn’t a verdict. That’s a life. It’s ours. And I am keeping it.