Friday morning, my phone rang. “Hi, Mom,” Ezra said, in that careful tone men use when rehearsing a kindness that’s really a cut. “About tonight… I’m sorry, but my wife wants dinner to be just her family.”

Just her family. As if forty-two birthdays, shoe-tying lessons, and feverish midnight math homework were an accounting error I could amend on Form 1040-X.

The tax code does not tolerate mistakes or inaccuracies. I spent forty-two years as an IRS inspector in Carson City, and these principles are ingrained in my blood.

Today, when I look in the mirror, I see the same Abigail Tmaine. Gray hair pulled back in a tight bun, deep wrinkles around eyes and lips that almost never smile, arms with protruding veins, but still strong enough to dig a small vegetable garden behind the house by myself. Seventy-eight years old, and I still manage on my own.

My home on a quiet Carson City street is more than just walls. It’s a place where everything has its own meaning and story. The pictures on the walls tell of the life that once simmered here. Wallace with his perpetual pipe. Little Ezra on his bike. Me in a strict suit against the backdrop of the IRS building. Now the house seems too big for a lonely old woman. But I’ve never complained about it out loud. Complaining is not in my nature.

“Abigail Tmaine, the Iron Lady of the IRS,” is what my co‑workers called me. I can’t say I took offense to that. My reputation as a relentless inspector protected me from the world. When you are a woman in the world of numbers and tax returns, it is better to be iron than soft. Softness is mistaken for weakness, and weakness is not respected in this world.

Wallace was the only one who saw the real me behind that iron mask. He worked for a construction company designing bridges and roads. We met when his firm was undergoing a tax audit. He didn’t try to charm me or bribe me like so many people did. Instead, he argued with me about tax deductions with such passion that I couldn’t help but marvel. Six months later, we were married to the surprise of everyone who knew us.

We lived together twenty‑eight years until lung cancer took him ten years ago. “Smoked a pipe too much,” the doctor said. But I know it wasn’t just that. He was the kind of man who burns brightly but doesn’t last long.

“Life isn’t about the number of years, Abby. It’s about what you’ve accomplished in the time allotted,” he liked to say.

Wallace accomplished many things, built several bridges that still stand today, raised a son, and left behind memories that warm me on lonely evenings.

Ezra is our only son. We gave birth to him late when I was already thirty‑six.

“Better late than never,” Wallace joked. Though I know he dreamed of having a big family. Maybe I resisted the idea for too long, afraid motherhood would interfere with my career. When Ezra finally came along, I was already a chief inspector of reputation and standing.

I raised him the way I thought was right, with discipline and demanding behavior. Some people called me strict, but I just wanted my son to be ready for the real world. The world doesn’t offer indulgences, so why accustom a child to something he’ll never get.

Wallace was gentler with his, “How about we let the boy, and he’s just a kid, Abby?” But when it came to parenting, I was adamant.

Ezra grew up sensitive and gentle, more like his father than me. He chose a career as a municipal water engineer—technical, but not overly ambitious. I had hoped he would go into law or finance where my connections could help him. But he had always loved water—lakes, rivers; even ordinary puddles after rain had mesmerized him as a child.

“Water is life, Mom,” he explained his choice of profession to me.

“And taxes are death,” I joked at the time.

But Ezra didn’t understand my irony. He’d never understood it.

Eight years ago, he brought Evet Bington into the house, a frail girl with cold eyes and a perpetual half‑smile, as if she knew something others didn’t. She worked as a receptionist in a dental clinic—a position that seemed inadequate for a woman with ambition read in her every move.

“She’s amazing, Mom,” Ezra said, looking at her with loving eyes.

I saw the calculation in her, but I kept silent. Is it right for a mother to criticize her son’s choices? It would be a sure way to alienate him.

The wedding was modest at Carson City City Hall, followed by dinner at a local restaurant. I paid most of the expenses. Although Ivet’s parents, Lewis and Doris Bington, were not tight on funds. Lewis worked as an insurance agent, Doris as a school teacher. Ordinary middle‑class people, unremarkable at first glance.

Soon after the wedding, I noticed that Ezra began to change, or rather his attitude toward me. At first, it was small things. He called less often, canceled visits at the last minute, was distant at family gatherings. Then came the comparisons.

“You know, Mom, Ivet’s parents never made her study accounting when she wanted to be a photographer,” he said once when I suggested he consider a promotion.

“I never forced you to become an accountant,” I objected.

“But you always wanted me to be someone else, not who I am,” he replied with a resentment he appeared to have carried for years.

Another time he stated, “And Ivet’s daddy always says that a modern parent should first and foremost be a friend to his child.” This was after I expressed doubt about the appropriateness of their decision to take out a loan for a new car.

“I can’t be your friend, Ezra. I’m your mother. Those are different roles,” I said at the time.

“Exactly. You’ve always been only a mother, never a friend.”

These comparisons to Ivet’s parents became a regular occurrence.

“Doris taught Ivette how to make this pie. She never hides her recipes, unlike some people,” he remarked at one family dinner when I refused to reveal the secret of my apple pie, saying the recipe would die with me.

Every such comparison was a little needle stabbing into my heart. I never showed how much it hurt me to hear that other people’s parents were better than me at everything. My pride wouldn’t let me.

And then Hope was born. My only granddaughter. The highlight of my life since Wallace’s death. She’s twenty‑one now, studying environmental science in college. A serious, smart girl with Wallace’s eyes and my stubborn chin.

Hope is the only one I have a real connection with in this family. We’ve never been close in the usual sense of the word—no secrets told in whispers, no long intimate conversations. But there is a tacit understanding between us. She sees me for who I am without judgment or idealization.

The last year has been particularly difficult. Ivet has become even more active in distancing my son from me. Calls became infrequent. Visits, a formality on holidays. Hope told me that her mother was constantly making excuses not to come to see me: she was too busy or tired or just not in the mood to see your grandmother.

“She thinks you’re a difficult person, Grandma,” Hope said honestly.

“I am a difficult person,” I replied with a bitter smile.

The final blow came three weeks ago when Ezra called to announce his forty‑second birthday.

“We’re going to celebrate modestly, just family,” he said.

“I can make your favorite chocolate cake,” I offered.

“Oh, don’t worry. Ivette’s mom already promised to bake it. She makes an amazing cake, moist with real cream. You know she never uses margarine in baking. Says it’s disrespectful to guests.”

Another comparison. Another needle. I do use margarine instead of butter sometimes—a habit of saving money developed over years of living on a tight budget.

“Sure, whatever you say,” was all I could reply.

After that conversation, I sat in the kitchen for a long time, looking out the window at my little garden. Wallace always said I was too proud, that I needed to learn how to show my feelings. But how do you show feelings to a son who sees only mistakes in me and only virtues in other people’s parents?

And that’s when it hit me. I would show him that I, too, can be generous, that I, too, can make grand gestures. I’d pay for dinner at the best restaurant in town for his birthday. Not that diner where they usually celebrate the holidays, but a real restaurant—the Silver Moose—where the average bill per person is over $100.

I pulled my stash out of the closet—the money I’d been saving for years for a rainy day. Ten thousand dollars in cash in an old cookie tin. I never fully trusted banks, despite all the tax breaks on deposits.

“What do you say to that, Doris Bington?” I muttered, thumbing through the bills. Lewis, with his modest insurance‑agent salary, would never be able to afford such a gift. For the first time in a long time, I felt a surge of energy. I’m going to show my son what true generosity means. I’ll prove that I can be as good as—no, better—than those Bingtons with their real‑butter pies and their advice on modern parenting.

That same evening, I called Ezra.

“I have a birthday surprise for you,” I said, trying to make my voice sound nonchalant.

“Really? What kind?” I could hear the surprise in his voice.

“I made reservations at the Silver Moose for the whole family for eight o’clock next Friday night.”

The silence on the other end of the wire lasted a few seconds.

“Wow, Mom, that’s… that’s very generous, but are you sure? This restaurant is pretty expensive.”

“I’m not poor, Ezra. I can afford to treat my only son and his family to a nice restaurant once a year.”

“Of course, of course. It’s just unexpected. Thanks. I’ll let Ivette and Hope know.”

When we finished talking, I felt a slight unease. His reaction wasn’t as enthusiastic as I’d expected, but perhaps he was just stunned. After all, I’d never made such grand gestures before. I walked over to Wallace’s picture on the mantle and said quietly, “See, I know how to change even at seventy‑eight.” The picture was silent, but I thought Wallace was smiling approvingly from behind the glass of the frame. He always thought I was too hard on myself and others. Maybe it’s time to change that.

Tomorrow, I would go to the restaurant in person to pay the deposit and make sure everything was perfect. I’d show Ezra that his mother knows how to appreciate beautiful gestures and family celebrations, too. I’d prove I’m as good as the Bingtons. After all, there’s more to us than pies with real butter. We’re bound by blood, shared memories, and love. At least on my end.

The Silver Moose was located in the heart of Carson City in a historic building that once served as the city’s first bank. High ceilings, crystal chandeliers, marble columns—everything breathed luxury and tradition. I had always passed by this restaurant, even when I had money. I’d always thought it was an unjustifiable luxury to spend so much on food. But today, I pushed the heavy door open with determination and stepped inside.

A young man in an impeccable suit met me at the entrance.

“What can I do for you, ma’am?” he asked with a professional smile, glimpsing my conservative suit and classic shoes—discreet, but quality. I’d always adhered to the rule: better less, but better.

“I’d like to talk to the manager about reserving a table for next Friday,” I said in the firm voice I used during tax audits.

“Of course, ma’am. One minute.”

The wait was not a minute, but all of ten. I stood in the lobby looking at the pictures of celebrities visiting the restaurant. Governors, senators, famous actors—all of them smiled at the camera against the background of the Silver Moose logo.

Finally, the manager appeared—a tall man with graying temples and impeccable posture.

“Ms.—” he began.

“Mrs. Tmaine,” I corrected.

“I’d like to make a reservation for a table for four next Friday for eight o’clock in the evening. It’s my son’s birthday.”

“I’m afraid we already have all the tables booked for next Friday,” he said without even checking the book. “Perhaps two weeks from now?”

“I need next Friday exactly. It’s an important date for my family.”

“I understand, but—”

“I’m willing to pay more than usual. Double the price if necessary.”

His eyebrows raised slightly. He looked at me with renewed interest.

“Give me a minute,” he said, and stepped back to the counter. A short time later, he returned with the reservation book. “Surprisingly, we actually have a table free for eight o’clock tonight next to the window overlooking the capital. One of the best in the room.”

I held back a smile. Money really does solve a lot of problems.

“It’s going to be beautiful. How much do you need to put down as a down payment?”

“We usually charge twenty percent of the estimated bill.”

“What if I deposit fifty percent?” I asked. “Say five hundred dollars.”

“That’s more than enough, Mrs. Tmaine.” There was genuine respect in his voice. “Now, do you wish to order a special menu or will you leave the choice up to the guests?”

“I want everything available. A full menu, the finest wines, desserts, and a special cake to end the evening. Chocolate with raspberries.”

“Excellent choice. Our pastry chef is famous for his chocolate cakes.”

We discussed the details and I put down a deposit—five hundred in cash. I noticed the manager was a little surprised when I pulled the money out of my classic leather wallet, but he professionally concealed his reaction. Perhaps he expected me to pay with a card like most customers, but I’d always preferred cash—an old habit of a woman who’d seen how easily numbers changed in computer systems.

“We’ll do our best to make the evening perfect, Mrs. Tmaine,” he assured me goodbye.

Walking out of the restaurant, I felt different—more confident, more important—a feeling long forgotten. I rarely allowed myself to spend on luxuries, even when I could afford it. Always saving, saving, thinking ahead. Wallace often joked about my frugality.

“Abby, you save for a rainy day so diligently that it will never come.”

Maybe he was right.

On the way home, I reflected on my relationship with Ivette. It hadn’t gone well from the start, even though outwardly we both kept up appearances. I remember the first time Ezra brought her to our house. It was a warm spring day, and I had made my signature apple pie. Ivette was dressed simply but tastefully—beige pants, blue blouse, minimal makeup. She politely praised the house, the garden, and the pie. But in her eyes, I could see the appraisal—cold, calculating.

“What a charming house, Mrs. Tmaine,” she said, surveying the living room with its good, though unfashionable furniture and classic curtains. “So authentic. Everyone’s chasing modern design these days, and you’ve got real history here.”

I realized what she meant: old‑fashioned, not on trend. But I smiled and thanked her for the compliment. Ezra glowed with happiness, looking at both of us.

“See, Mom? I told you two would get along.”

After the engagement, Ivette began to visit us more often, but always kept her distance. She never asked my advice, never shared her plans or problems. When I offered to show her how to bake the apple pie that Ezra liked so much, she politely declined.

“Oh, that’s very nice of you. But I have so many recipes from my mom. She’s an amazing cook, you know.”

At the wedding, I met the Bingtons for the first time. Lewis is a short, overweight man with tired eyes and a permanent smile. Doris is a petite woman with perfect hair and manicure who speaks in a quiet but confident voice. Ordinary people, unremarkable. But Ezra looked at them with such admiration as if they were royalty.

After the wedding, I began to notice Ivette gradually distancing my son from me. At first, it was in small things. Ezra started calling less often. His visits became shorter. When I asked him why he didn’t stop by more often, he always cited being busy or tired. But then I began to notice a pattern. Every time I offered to do something together—dinner, a trip out of town, even just helping with chores—Ivette would find a reason why it was inconvenient or impossible.

“Sorry, Mom, but we’re going to Ivette’s parents’ house this weekend. It’s their wedding anniversary,” Ezra was saying.

“How about next weekend?” I suggested.

“I can’t promise. We have so many plans.”

And the conversation faded away.

It was especially painful to hear the constant comparisons to Ivette’s parents that Ezra wove into every conversation we had.

“You know, Ivette’s parents always take her on vacation with them. Even now,” he said once when I suggested he come with me for a weekend trip to the mountains like we did when he was a kid. “They believe family traditions should be upheld,” he said.

“We can uphold our tradition, too,” I replied.

“Yeah, but they have it somehow more natural, without obligation.”

Another time, when I noticed that their kitchen was in need of renovation, Ezra proudly announced, “Ivette’s parents helped us with the kitchen renovation—not with money, but with advice and contacts. Lewis knows a great contractor who did everything at a friendly price.”

I offered to help financially, but Ezra declined.

“No, Mom, we can handle it. Besides, Ivette wants us to do everything ourselves.”

The most painful moment was when I tried to give advice on raising little Hope. She was about three years old at the time and was beginning to show the stubbornness that characterizes that age.

I suggested a system of rewards and punishments that worked with Ezra.

“Mama never interferes in their family affairs, unlike you,” Ezra replied sharply. “She believes that each generation should raise their children in their own way without outside pressure.”

I stayed silent then, swallowing the offense. But since then, I tried not to give advice. Even when I saw it was necessary.

As I walked home from the restaurant, those memories replayed in my head like the frames of an old movie. I couldn’t understand the moment I lost touch with my own son. When did he start looking at me through Ivette’s eyes instead of his own?

At home, I got busy preparing for dinner. I pulled my best dress out of the closet—a dark blue long‑sleeved, modestly cut dress. I’d bought it five years ago at a good store, but I’d only worn it a couple of times. It hadn’t been the right occasion. I cleaned and ironed it. I found Wallace’s old brooch, the silver rose he’d given me for our twentieth wedding anniversary. I pulled out my low‑heeled shoes—classic, elegant, soft leather. I wanted to look dignified, as good as Doris Bington with her perfect manicure and styling. Maybe I couldn’t compete with her in modern looks or culinary talents, but I could show that I could be generous and thoughtful, too.

That evening, the phone rang. I saw Hope’s name on the screen and answered immediately.

“Grandma, it’s me.” Her voice sounded a little strained.

“Hello, sweetheart. How are you doing at college?”

“I’m fine, thank you. Listen, Dad said you’re having dinner at the Silver Moose for his birthday.”

“Yes, I made reservations for Friday for eight at night.”

“That’s… that’s very generous of you.”

“Nothing is too small for my only son,” I said, trying to sound casual.

A pause followed, during which I could hear Hope breathing into the tube, as if gathering her thoughts.

“Grandma, I don’t know how to say this. I think something is going on. Mom and Dad have been whispering a lot the last few days. When I come into the room, they stop talking right away.”

“Maybe they’re preparing a surprise for you,” I suggested, though my heart was already starting to beat anxiously.

“I don’t think so. I overheard part of the conversation by accident. They mentioned moving.”

“Moving?”

“They want to buy a new house—not just a new house. Mom said something about another state and about how now they’ll have a chance to start over without—” she stammered. “Without old attachments.”

I felt a chill go down my chest. Old attachments. Was that what they had called me?

“Are you sure you heard that right?” I asked, trying to keep my voice calm.

“Yes, Grandma. And also, Mom said they’re going to announce it after dinner on Dad’s birthday. She said it would be the perfect time for the news.”

I sat up, clutching my phone tightly. So, they were planning to use the dinner I’d paid for to announce their departure—to tell me they were leaving and taking my only granddaughter.

“What about you, Hope? Are you leaving, too?” I asked quietly.

“Yeah, I don’t know, Grandma. I have another year and a half of school left. If they move, I’ll have to decide whether to stay here alone or transfer to another college.”

“I understand,” I said, though inside everything was boiling with anger and resentment.

“Grandma, I shouldn’t have told you. They don’t know what I heard. Please don’t give me away.”

“Of course, dear. It will stay between us.”

We talked some more about her studies, about the new semester that was supposed to start in a month, but I was barely listening. My thoughts were far away. When we finished talking, I sat in silence for a long time, looking at Wallace’s picture.

What would he have done in my place? He’d always been more diplomatic, able to smooth over sharp edges, but even his patience had limits. I remembered how Ezra had joyfully announced his engagement to Ivette. How he’d introduced us to each other, hoping for a warm relationship. How gradually his eyes had begun to look at me differently—with criticism, with comparisons I’d always lost.

I remembered how at Hope’s christening, Doris Bington had bossed everyone around, arranging people for pictures, and put me so far away from the baby that I was barely visible in the pictures. How Ezra didn’t notice that—or pretended not to.

All these years, I kept quiet, swallowed my resentment, hoped things would get better with time. But time only made things worse. And now they were planning to cut me out of their lives for good. I looked at my phone, thinking about calling Ezra, asking him directly about his plans, but something stopped me. Pride, fear of hearing the truth, or just fatigue from the constant struggle to find a place in my own son’s life?

I decided to wait. Let things take their course. I paid for the dinner. I’d be there. And when they announced their plans, I’d be ready. For what exactly, I didn’t know yet. But one thing was certain: I would no longer swallow my resentment in silence. No more comparisons. No more humiliation. If they wanted to cut ties, I wouldn’t cling to them like a pathetic old woman. After all, I have my pride, too. And maybe it’s time to show them that.

Friday morning began as usual. I got up early, drank my coffee, and did chores around the house. I had been feeling a strange tension these past few days, like something was about to happen. Perhaps it was a premonition.

The phone rang around ten. Seeing Ezra’s name on the screen, I smiled involuntarily. Maybe he wanted to confirm the details of the evening or thank me for organizing dinner.

“Good morning, Ezra,” I said, trying to keep my voice upbeat.

“Hi, Mom.” I immediately heard the awkwardness in his voice. Not a good sign.

“Is something wrong?”

He was quiet for a few seconds, then sighed.

“Mom, there’s something I have to say about dinner tonight.”

I remained silent, feeling my heart start to beat faster.

“You see, I’m sorry, but my wife prefers to have just her family at dinner.”

I felt the room around me seem to sway.

“Only her family? Who am I then? I don’t understand, Ezra. I’m your mother. Aren’t I family?”

“Of course you’re family, Mom. But Ivette would like us to celebrate tonight with just her parents. They have some news. And, well, they want a special evening.”

“A special night?” I repeated. “At the restaurant I booked and paid for.”

“Yeah, about that. We could give you a refund or have another dinner later just for you.”

“Just for me?” Bitterness rose up inside, covering my eyes like arms.

“No, not at all, Mom. It’s just… Well, you know, Ivette’s got it all planned out a certain way and—”

“And I don’t fit into her plans.”

“See, it’s not like that.”

“How is it, Ezra? Explain it to me.”

He sighed again, and I could hear the irritation in his voice—the familiar irritation that came every time I disagreed with something about Ivette.

“You see, Mom, Ivette’s parents know when to be there for us and when to give us space. They never impose.”

There it was. Another comparison, another needle.

“So, I’m imposing?” I asked quietly.

“That’s not what I meant. It’s just that sometimes you can be too pushy, too present.”

Too present. Interesting wording for a mother who sees her son once a month. If she’s lucky.

“I understand,” I said, even though I didn’t really understand anything. “I’ll cancel the reservation.”

“No, don’t,” Ezra said quickly. “We’ll use it—just without you.”

Now, that was when the real resentment hit me. They weren’t just refusing my presence. They wanted to use my gift without me.

“Okay,” I said, marveling at how calm my voice sounded when everything was churning inside. “I hope you have a good time.”

“Mom, no offense, please. We’ll be sure to have a separate evening for you. Maybe next week.”

“Of course, Ezra. Next week.”

We said our goodbyes and I hung up. For a few minutes, I just sat there staring into space. Then I slowly got up and walked to the kitchen. I put the kettle on mechanically and took out a cup. Everything seemed unreal, as if in a fog.

“My wife prefers to have only her family for dinner.” Just her family. Like I’m not family, like I’m nobody.

The kettle boiled, but I forgot about it. Memories came flooding back to me—all the times they had subtly but insistently pushed me aside; all the times Ezra had taken her side, betraying our connection. I remembered how he hadn’t invited me to an important job interview, even though I could have given him valuable advice.

“Ivette thinks I should handle it on my own,” he’d said.

Then I remembered how he refused to take the money I offered for the down payment on their house because Ivette’s parents had already promised to help, and they never take interest. Each memory was a drop of poison, poisoning my heart. But the final insult—to exclude me from a holiday I had organized and paid for myself—was too much.

I called the restaurant and cancelled the reservation. The manager was surprised.

“But, Mrs. Tmaine, everything is already set. The pastry chef has already started work on the cake.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, “but circumstances have changed.”

“Of course. We’ll refund your advance, but according to our policy, we retain thirty percent if you cancel in less than twenty‑four hours.”

“I understand.”

“Do you want us to transfer the money to your card or—”

“No,” I suddenly decided. “Donate it to the local homeless shelter.”

“Excuse me?”

“You heard me. Give that money to someone who needs it more than I do.”

After that conversation, I felt a strange sense of relief, like I had finally done something for myself instead of for others—something that didn’t fit the mold of the proper, predictable Abigail Tmaine.

I decided to walk around town to clear my head. Carson City is small and I know every corner here. I walked past the stores, past the city park, past the municipal building where Wallace once worked. People said hello to me. In four decades at the IRS, I’d become a well‑known figure in town. I nodded back, but didn’t stop to talk.

My feet led me to the home of Martha Higgins, my neighbor for over thirty years. Martha is the only person I could call a friend, though we’ve never been particularly close—just two elderly women who sometimes have tea together and discuss local news. Martha cheered when she saw me.

“Abigail, what a pleasant surprise. Come in. I was just baking a blueberry pie.”

We sat in her neat kitchen drinking tea and eating the pie. I wasn’t going to talk about what had happened. Pride wouldn’t let me admit that my own son had rejected me. But Martha was always observant.

“Is something wrong, Abby? You look pale.”

And then I couldn’t take it anymore. The words came pouring out—about the restaurant, about Ezra’s call, about what he’d said.

“‘My wife prefers her family to be the only ones at dinner,’” I repeated bitterly. “Can you imagine? Just her family.”

Martha shook her head.

“That one always struck me as arrogant. Remember how she refused to participate in the charity fair last year? Said it was too provincial.”

I nodded, swallowing back tears. Pride still wouldn’t let me cry even in front of Martha.

“You know,” Martha continued, “my Jenny works for the same plumbing company as Ezra—not in the same department, but they cross paths in meetings sometimes.”

“I knew that.” Jenny, Martha’s daughter, was an environmental engineer and sometimes told her mother about the job.

“So Jenny says everyone at the company is talking about how Ezra applied for a transfer to the Portland branch. In Portland. In Oregon.”

I felt the ground go from under my feet.

“Yes—In about two months. He’s being transferred there with a promotion. He’s going to be in charge of some new water purification project.”

I was silent, trying to make sense of what I was hearing. Portland—eight hundred miles from here, in another state.

“Jenny said everyone was surprised because Ezra never aspired to leadership positions, but his wife…” Martha fiddled. “His wife, they said, insisted. Said Portland had better schools for Hope and that her parents were thinking of moving there, too.”

“Ivette’s parents are moving, too?” I asked, feeling nausea rising to my throat.

“Looks like it. Jenny heard Ezra tell someone on the phone that Ivette’s parents always know the best thing to do and that they’ll help with the down payment on a new house in some upscale neighborhood.”

Now everything fell into place. Hope was talking about moving. Ezra and Ivette were whispering. A dinner at a restaurant I wasn’t supposed to attend. They were planning to announce the move and didn’t want me there so I wouldn’t ruin their celebration with my reaction.

“They’re going to leave and they didn’t tell me,” I said out loud.

Martha took my hand.

“Abby, I didn’t mean to upset you. I just thought you should know.”

“Thank you, Martha. You did the right thing.”

I finished my tea and stood up. A strange calmness possessed me—the calmness of someone who finally sees the whole picture.

“Where are you going?” Martha asked, looking at me worriedly.

“There’s something I need to do,” I replied. “Thanks for the tea, and for the information.”

I walked home at a brisk pace, not feeling tired despite my age. Thoughts swirled in my head, forming into a plan of action. Do they want to cut all ties? Start a new life without old attachments? Fine. But they won’t get anything from me.

At home, the first thing I did was pull out my will. After Wallace died, I changed it, leaving everything to Ezra: the house, the savings, even the collection of porcelain figurines I’d started collecting when I was young. At the time, it seemed right to provide for my son after my death. Now, I looked at the document with different eyes. Why should I leave everything to a man who cuts me out of his life, who allows his wife to treat me like an outsider?

I picked up my phone and dialed the number of Harold Finch, the attorney who had handled my cases for the past twenty years.

“Harold, this is Abigail Tmaine. I need to meet with you urgently today, if possible.”

“It’s Friday, Abigail, and it’s almost four. I was going to leave early.”

“This is very important, Harold. This is about a complete change in my will.”

He was silent for a second.

“All right. Come by in half an hour, but be aware that it may take longer to complete all the paperwork.”

“I understand, but I want to start the process today.”

Exactly thirty minutes later, I was sitting in Harold Finch’s office explaining my intentions. He listened attentively, occasionally making notes.

“Are you sure, Abigail? This is a radical change.”

“Absolutely sure. I want my house to go into the ownership of the Carson City Single Senior Citizens Foundation upon my death. All of my savings, except for ten thousand dollars for my granddaughter, Hope, should also go to the foundation.”

“And your son?”

“Nothing to him.”

Harold shook his head.

“I must warn you that such a will can be contested. The complete disinheritance of a direct descendant—”

“I’m not disinheriting him completely. Let him have my porcelain collection. It’s worth quite a lot.”

“Still, the court may find it insufficient.”

“Then make a deed of gift of the house. Right now. I give the house to the foundation but retain the right of occupancy until my death.”

Harold raised his eyebrows in surprise.

“That’s a big step, Abigail. You won’t be able to undo it later.”

“I know. That’s exactly what I want.”

He looked at me for a long moment, then nodded.

“Good. I’ll get the paperwork ready, but the deed of gift will require a notary, and at a time like this…” He checked his watch. “My niece Rachel is a notary. She can come if you call her.”

The next two hours passed in paperwork. Harold drafted documents, made phone calls, consulted with colleagues. Rachel arrived—the daughter of my late sister, with whom we weren’t particularly close, but kept in touch. She was surprised by my decision, but didn’t ask too many questions.

By seven, everything was ready. I signed a gift of the house in favor of the foundation with the right to live in it for life. I signed a new will that also gave most of my savings to the foundation, ten thousand to Hope, and the china collection to Ezra.

“The documents will take effect immediately,” Harold said, handing me copies. “Are you sure you don’t want to think it over again?”

“No, Harold. I’ve made up my mind.”

On the way home, I felt strangely light. It was as if a great weight had been lifted from my shoulders. I was no longer bound by obligations to a son who didn’t appreciate those obligations. I was free.

At home, I neatly folded the copies of the documents into a folder and placed it on the coffee table in the living room. Then I took a shower, drank a cup of tea, and sat in my favorite chair by the window. It was almost nine in the evening. The Silver Moose was probably serving main courses by now. Maybe they had already announced the move. Maybe they were raising their glasses to a new life—a life without me.

I looked at Wallace’s picture.

“What would you say now, darling? Would you approve of my decision?”

The picture was silent, but I thought I saw understanding in Wallace’s eyes. He always said, “There comes a moment in life when you have to let go.” Maybe for me, that moment had come now.

I sat in silence, waiting for my son’s family to return from dinner. They had promised to stop by after the restaurant—probably to soften the blow of their decision to move. They didn’t know I already knew everything. Didn’t know I had news for them, too. I had the paperwork ready to show my son and daughter‑in‑law. Let them see that their decision was not without consequences. Let them realize that you can’t cut people out of your life with impunity.

Time dragged agonizingly slow. I sat in the living room staring at the antique clock I’d gotten from my grandmother—another family heirloom that Ezra wouldn’t get now. The hands were showing the beginning of eleven. The restaurant must have served dessert by now. Probably not the chocolate cake I’d ordered, but something else Ivette had chosen. She always thought she knew best.

Outside the window, dusk was thickening. Summer evenings in Carson City are long and warm, but even the longest day comes to an end. I didn’t turn on the light. I like sitting in the semidarkness alone with my thoughts. Those thoughts went back to the past—to the years when Ezra was little and I was his whole world. I remembered teaching him how to tie his shoelaces, how I read to him before bed, how I helped him with his homework. I always put discipline first, maybe too often. Perhaps I really was stricter than I should have been.

Was I a good mother? This question haunted me for years. I loved my son, always wanting the best for him. But love can be shown in many different ways, and perhaps my way didn’t match what Ezra needed.

I remember him bringing home a drawing once, back in elementary school—a simple childhood sketch of our family. Wallace was depicted as tall and smiling with must hair and big hands. Ezra drew himself small with a ball in his hands. And I— I was almost as tall as Wallace, with a straight back and tightly compressed lips, without a smile.

“Why did you draw Mom so serious?” Wallace asked then.

“Because Mom is always serious,” Ezra replied. “She rarely laughs.”

That hurt me, but I didn’t show any sign of it. Instead, I hung the drawing on the refrigerator and tried to smile at my son more often. But I guess the first impression had already been made.

When Ezra became a teenager, our relationship became more complicated. He wanted more freedom and I insisted on rules.

“You’re suffocating him, Abby,” Wallace said. “Let the boy breathe.”

But I was afraid that without strict supervision, Ezra would lose his way like so many teenagers in our town. When he turned sixteen, we had a big fight over a party he wanted to go to. I knew there would be alcohol there, so I forbade him to go. He went anyway, sneaking out the window. Wallace found him at three in the morning at the bus stop—slightly drunk and very scared.

“I don’t want you to end up like me,” Wallace told me that night, when Ezra was already asleep. “My mother was strict, too, and it only drove us further apart. Don’t make the same mistakes she did.”

I tried to change, to be gentler, but Ezra’s formative years had already passed, and our way of communicating was settled. He saw me as a controller, not an ally. Maybe that’s why the Bingtons won his heart so easily. They were the exact opposite of me—relaxed, outwardly accepting, generous with praise. They didn’t know Ezra as a teenager, didn’t see his mistakes and weaknesses. It was easy for them to be the perfect parents to a mature, formed adult.

I remember when these comparisons began. It was shortly after the wedding, when Ezra and I returned from a short honeymoon in San Francisco. We met for Sunday dinner and Ezra was talking about the trip.

“Ivette’s parents gave us a list of the best restaurants in town,” he said. “And they even made reservations for us at the Blue Moose, which is such a swanky waterfront restaurant.”

“That’s very nice of them,” I replied.

“Yes, they’re always thinking of things like that. Remember, Mom, when we went to San Francisco when I was twelve, we ate at that diner by the motel, and I had an upset stomach afterward.”

That was the first stone. Small, almost unnoticeable, but it started an avalanche. Then there was the crib incident when Hope was born. I offered to give away Ezra’s crib that I kept in the attic.

“Thanks, Mom, but Ivette’s parents already bought us a new one. They think everything should be new and modern for a baby. Besides, modern cribs are safer.”

Another rock. And then they began to fall one by one.

“Ivette’s parents think children should be put in daycare as early as possible so they learn to socialize.”

“Ivette’s dad says that at our age it’s time to start thinking about owning our own house instead of renting an apartment.”

“Ivette’s mom taught Ivette this recipe. She says a real hostess should be able to cook without a book.”

Every time Ivette’s parents sounded, I inwardly cringed. Each time I felt like I was losing in an unspoken competition I didn’t even want. As the years went by, the comparisons became more direct and more painful.

“Ivette’s parents never forced her to do anything she didn’t like.”

“Ivette’s parents always supported her decisions, even if they didn’t agree with them.”

“Ivette’s parents believed that the best gift for a child is freedom of choice.”

Somehow, in Ezra’s eyes, I had become the embodiment of everything Ivette’s parents were not—controlling, critical, outdated in my views. And the more he exalted them, the worse I felt. Maybe I really was a bad mother. Maybe I really was too controlling, too pressuring, too critical of him. These doubts gnawed at me for years, forcing me to back down, to give in, to be silent when I wanted to scream.

But today, that was going to change.

The sound of a car pulling up pulled me out of my musings. I tensed, listening to the voices outside—laughter, excited exclamations. They were clearly in a good mood. The restaurant I’d paid for had lived up to their expectations.

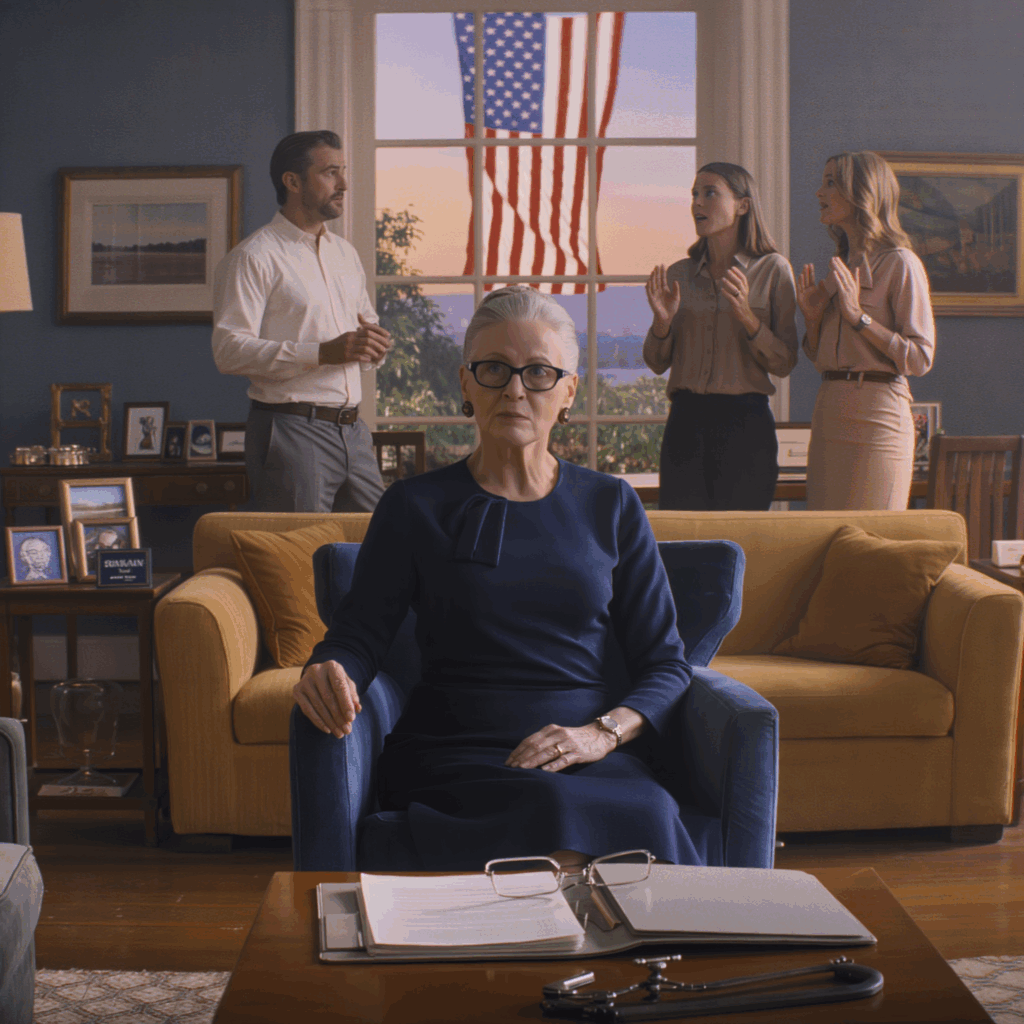

The doorbell rang three times. Ezra had always rung it that way, ever since he was a kid. I got up, turned on the light in the living room, and went to open it.

All three of them were there—Ezra in the suit I’d seen him in last Christmas, Ivette in an elegant blue dress, and Hope shuffling awkwardly from foot to foot in a simple black dress. Everyone’s faces were flushed, whether from the wine or the excitement.

“Mom.” Ezra smiled broadly as if he wasn’t the one who had informed me hours ago that I didn’t fit into their family circle. “We decided to stop by your place after dinner.”

“That’s very nice of you,” I said, trying to keep my voice neutral. “Come on in.”

They entered the house—a house that was no longer mine, though they didn’t know it yet. Ivette looked around with the usual slight disdain that always slipped into her gaze when she visited me. Hope glanced at me quickly, and I could see the concern in her eyes.

“How was dinner?” I asked as we settled into the living room.

“Delicious,” Ivette exclaimed. “The Silver Moose really lives up to its reputation. The steaks were just melt‑in‑your‑mouth.”

“Delicious—and the wine.” Ezra cleared his throat. “Too bad you weren’t with us, Mom.”

“Really?” I raised an eyebrow. “I thought my presence was unwelcome.”

There was an awkward pause. Ivette blushed slightly but quickly pulled herself together.

“Abigail, we just wanted to spend this evening in a small circle. We had a special reason.”

“Yes, Mother,” Ezra picked up on that. “We wanted to break the news to Ivette’s parents in private and then tell you.”

“What news?” I asked, even though I knew the answer perfectly well.

Ezra and Ivette looked at each other, their faces glowing.

“We’re being transferred to Portland,” Ezra announced. “I’ve gotten a promotion. I’ll be in charge of a new water treatment project in the Columbia River area. This is a huge opportunity for me—for all of us.”

“Congratulations,” I said. “When are you leaving?”

“In two months,” Ivette replied. “Got to sell the house in time, find a new one in Portland, transfer Hope to college there.”

“Yeah, so much to do,” Ezra chimed in. “But Ivette’s parents will help us. They’re thinking of moving to Portland, too. Can you imagine? Lewis says the climate there is better for his arthritis, and Doris has always wanted to live closer to the ocean.”

I listened to them, and every word was like a blow. They’d planned everything, decided everything, and never once thought about the fact that I’d be alone here—that my only family would be hundreds of miles away.

“And you decided to tell me this after you celebrated with Ivette’s parents?” I asked, not hiding my bitterness.

Ezra looked embarrassed.

“Mom, we wanted to tell you right away, but… well, you would have been upset. We thought it would be better to celebrate everything first and then talk to you calmly—”

“So I wouldn’t ruin the celebration with my upset.”

“Abigail,” Ivette interjected. “We realize this isn’t going to be easy for you, but you have to realize that this is a huge opportunity for Ezra. His career—”

“His career has never been more important to me than his happiness,” I interrupted. “And I thought his happiness included me.”

“Of course it does, Mom,” Ezra exclaimed. “We’ll come for the holidays. You can visit us.”

“How do your parents visit you, Ivette? Once a month? Once a week?”

Ivette tensed.

“My parents respect our privacy. They come when we invite them.”

“And you’re going to invite me?”

“Mom, stop it,” Ezra started to get annoyed. “You’re dramatizing everything like you always do. We’re not leaving you. We’re just moving. People do it all the time.”

“People leave their elderly parents all the time?” I asked quietly.

“We don’t abandon you,” Ezra was almost yelling now. “Why do you always make everything so complicated? Why can’t you just be happy for me like Ivette’s parents? They supported us right away— even offered to help with the down payment on the house.”

There it was—another comparison. Even now. Even in this moment.

“You know, Ezra,” I said, surprised at the calmness in my voice, “I’ve made some decisions today, too.”

I stood up and picked up a file folder from the coffee table.

“What’s this?” Ezra asked, suddenly wary.

“My new will and a deed of gift for the house.”

“A deed of gift? You’re selling the house?” He looked shocked.

“No. I’m donating it to the Carson City Single Senior Citizens Foundation with the right of lifetime residency for me.”

There was dead silence. Ezra and Ivette stared at me as if I’d suddenly spoken a foreign language.

“You what?” Ezra finally squeezed out.

“You heard me. I’m donating the house to a charitable foundation. After I die, they will use it as a daycare center for the elderly, and I’m bequaving most of my savings to the foundation as well.”

Ezra’s face turned white as chalk. Ivette froze, her eyes widening with shock.

“But—but why?” Ezra asked in a trembling voice.

“Because I’m tired of being the old attachment that you want to get rid of. Because I’m tired of being constantly compared to Ivette’s perfect parents. Because you’re going to Portland without asking me, without thinking about me—and I don’t have to think about you anymore.”

“Mom, you can’t do that.” He grabbed the papers, started frantically going through them. “This is our family home. I grew up here, and now you’re going to grow out of it for good. You’re going to start a new life in Portland without your old attachments.”

“Have you been eavesdropping on our conversations?” Ivette asked sharply.

“No. But in a small town, walls have ears.”

Ezra continued to look through the papers, his hands trembling.

“You’re leaving me a… porcelain collection?” His voice trailed off. “That’s it? After all these years?”

“What did you expect, Ezra? That I’d sit here, a lonely old woman waiting for your rare visits? That I’d call you and listen to you talk about how wonderful Ivette’s parents are, helping you get settled in Portland? No, thank you. I prefer to dispose of my property as I see fit.”

“That’s— This is crazy,” Ivette finally found her voice. “You can’t just take your own son’s inheritance and disinherit him.”

“I can, and I did.”

“We’ll challenge it in court,” she almost shouted. “This is clearly the decision of an unstable person.”

“Go ahead,” I shrugged. “Just keep in mind that I’ve been with the IRS for forty‑two years. I know every judge in this town, and every one of them knows me as a paragon of mental health and mental clarity.”

Ezra lowered his head, holding on to the documents like a lifeline.

“Mom, please… let’s talk about this. You can’t—”

“I’ve already done everything, Ezra. The papers are signed and certified. The deed of gift on the house went into effect today. The will has been changed. I’m leaving ten thousand dollars to Hope and the rest to the foundation.”

At the mention of my granddaughter’s name, everyone turned to look at her. Hope sat quietly in the corner of the couch, watching with wide‑open eyes.

“Hope, say something,” Ivette demanded. “Your grandmother has lost her mind.”

Hope rose slowly. Her face was serious, her gaze hard.

“Actually, I think Grandma has every right to dispose of her property,” she said calmly.

“What?” Ivette stared at her daughter in disbelief.

“Mom, Dad—for years, you’ve been treating Grandma like a… like a burden. I’ve seen it. I’ve heard you talk about her when she’s not around. How you planned this move without even thinking about what it would be like for her.”

“Hope, you don’t understand—” Ezra began.

“No, you’re the one who doesn’t understand.” For the first time, there was real anger in Hope’s voice. “You’re constantly comparing Grandma to Grandma and Grandpa Bington—and always not in her favor. You criticize her for everything. The way she talks, the way she dresses, the way she cooks. You sideline her at every opportunity. And now you’re surprised she won’t leave you everything she has?”

Ivette and Ezra looked at their daughter with their mouths open. I was surprised, too. Never before had Hope spoken so openly and harshly.

“I’m tired of it,” she continued. “Tired of hearing you exalt Grandma and Grandpa Bington—who, by the way, aren’t perfect either. Do you know that Grandpa Lewis lost half his savings on some dubious investments last summer? Or that Grandma Doris secretly smokes, even though she’s always criticizing others for their bad habits? They’re ordinary people with their own flaws—but for some reason, you’ve decided to make them perfect and Grandma Abigail a monster.”

A heavy silence hung in the room. Ezra looked at his daughter as if seeing her for the first time. Ivette pressed her lips into a thin line.

“You don’t know what you’re talking about,” she finally uttered. “We always wanted what was best.”

“Better for whom, Mother? For Grandma Abigail—or for yourself?”

Ezra shifted his gaze from his daughter to me. In his eyes I read confusion, shock, disbelief. He’d never seen me like this—determined, unyielding, capable of drastic action. And he’d never seen his daughter like that.

“Mom,” he said quietly. “Did you really do it? Really gave away the house and the money? It’s not a bluff?”

“No, Ezra, it’s not a bluff,” I replied. “I did what I think is right. Just like you do what you think is right for you.”

He lowered his head, hiding his eyes.

“I didn’t think you’d take our move so personally.”

“How else am I supposed to take the fact that my only family is moving hundreds of miles away without even discussing it with me?”

“We were going to discuss it today. After we decided everything. After celebrating with Ivette’s parents. After excluding you from—” He stopped. “After…”

“After excluding me from the family circle,” I finished for him.

Ezra couldn’t find anything to answer. Ivette sat with her arms crossed over her chest, her face stony. Hope stood between us, glancing back and forth at her parents and then at me.

“What now?” Ezra finally asked.

“Now you go to Portland, start a new life, and I’m staying here in my house, which is now owned by the foundation, and starting a new life, too.”

“Without us?”

“You’re the one who decided to be without me, Ezra. I’m just accepting your decision.”

The next two weeks passed in heavy silence. After that night, Ezra and Ivette left my house, slamming the door and promising to deal with this madness. Hope stayed with me, silently packing up some things and asking permission to sleep in her old room. I, of course, agreed.

Ezra called three times. The first time was the next morning, to tell me that I was making a huge mistake and would regret my decision. The second, three days later, in a calmer tone—asking if there was anything I could do to revoke the gift. I replied that no, you can’t. The third call was a week later, informing me that he and Ivette were moving to Portland anyway, even without my financial help—which, it turns out, they had expected to receive.

“We’ll manage on our own,” he said. Then there was resentment—and something else in his voice. Maybe, for the first time in a long time, respect.

Ivette didn’t call at all. Hope told me that her mother was furious and thought I was a vindictive old woman determined to ruin their lives.

“She says you did it out of spite,” Hope said over a cup of tea. “But I explained to her that you simply made a decision about your property, just as they made a decision about moving.”

“And what did she say?”

“That it was a different matter entirely. That their move was a career opportunity and your decision was pure revenge.”

I shrugged. Let her think what she wants. In truth, I felt no gloating or satisfaction at my action—just a strange calmness, as if I’d finally shed the heavy weight I’d been carrying for years.

A month after our confrontation, I learned from Martha that Ezra and Ivette’s house was for sale. The price was low. They were clearly in a hurry.

“Jenny says they’re in a difficult financial situation,” Martha informed me over our usual tea party. “Ivette’s parents refused to help with the down payment on the house in Portland. Something about them having their own problems there.”

I nodded, feeling neither surprised nor schadenfreude. It was just information—another fact in a chain of events.

Hope, meanwhile, had decided to stay in Carson City. She’d applied to transfer to a local college so she could finish her degree here.

“Are you sure?” I asked her. “It’s your parents who are leaving, not mine. You don’t have to stay because of me.”

“I’m not staying because of you, Grandma,” she replied with a slight smile. “Though your company is a nice bonus. It’s just that I realized I don’t want to depend on my parents. I want to build my life on my own. And I already have friends here—teachers who know me. Why give it all up?”

I looked at my granddaughter and saw myself in her—young, determined, independent. But unlike me, Hope knew how to be soft without losing her strength. It was a trait I had always lacked.

“I’m proud of you,” I told her.

“Thank you, Grandma,” she smiled. “I’m proud of you, too.”

Ezra and Ivette left at the end of August. They didn’t come to say goodbye. Hope told me that her mother insisted on a quick departure without too much of a scene. Ezra wanted to stop by, but ended up just calling from the car, already leaving town.

“We’re leaving, Mom,” he said. “I hope you won’t be mad for too long.”

“I’m not mad, Ezra,” I replied honestly. “I’ve just accepted reality as it is.”

“Okay, well… bye. I’ll call you when we’re settled.”

He didn’t call a week or a month later. I wasn’t surprised or upset. It was expected. He’d always taken the path of least resistance, and maintaining a relationship with me now required effort he didn’t want to put in.

In the fall, Hope moved into a small apartment closer to the college, but she visited me often. We ate lunch together on weekends, sometimes went to the movies, or just walked through the park. She told me about her studies, about her new friends, about her plans for the future. I listened and gave advice only when she asked.

“You know, Grandma,” she once said, “you’re not at all like my parents described you. They always said you were controlling and critical, but you’re not like that with me.”

“Maybe I’ve changed,” I replied. “Or maybe it’s easier for me to be myself with you because you’re not comparing me to someone else.”

She hesitated.

“I guess that’s probably true. Comparisons hurt, even when people don’t realize it.”

In October, I first came to the Foundation for Single Seniors—the organization to which I bequeathed my home. The foundation’s director, Ellaner Paige—a woman about my age, but with the energy of a forty‑year‑old—welcomed me with open arms.

“Mrs. Tmaine, we are so grateful for your gift. It will help so many people.”

She showed me the daycare center where seniors could socialize, do crafts, and play board games. Many of them were all alone. Their children were either out of town or too busy with their own affairs to visit their parents regularly.

“Would you like to join us as a volunteer?” Ellaner asked. “We always need people with life experience who can support our wards.”

I agreed, not expecting myself to be so willing. And soon I found myself traveling to the center three days a week to help with bookkeeping. My skills as a tax preparer proved to be very useful. I taught financial‑literacy classes for the elderly and simply talked to those who had no one to talk to. It was a new chapter in my life—unexpected, but fulfilling in a way I hadn’t experienced in years.

It had been a snowy winter in Carson City. I often thought about what it was like for Ezra and Ivette in rainy Portland. I knew from Hope that things weren’t going well for them. Ezra’s job wasn’t as interesting as he’d expected, and Ivette couldn’t find a position that matched her ambitions.

“They fight all the time,” Hope told me after one of the rare phone calls with her parents. “Mom accuses Dad of not trying hard enough, and Dad says she’s demanding too much.”

I listened without commenting. It was their life, their choices, their problems. I no longer felt responsible for Ezra’s happiness. It was a strange, almost frightening sense of freedom.

In the spring, Hope received a grant for an ecological study at a local nature preserve. She glowed with happiness as she told me about her project.

“It’s all because of you, Grandma. If I had left with my parents, I never would have gotten this opportunity.”

“You got it because of your effort and talent,” I countered. “I had nothing to do with it.”

“Yes, you did. You showed me that it’s possible to stand your ground even when everyone around you is pushing. That you can be strong without being cruel. I’ve learned a lot from you this year.”

Her words touched me to the core. For the first time, I felt that maybe I wasn’t such a bad mother. It was just that Ezra needed a different kind of mother—a softer, more compliant one. And Hope, with her strong character and independent mind, needed exactly the kind of example I could give her.

The summer brought new changes. Ellaner offered me the position of chief financial officer at the foundation—a paid position albeit with a small salary.

“You’re a perfect fit, Abigail. You have a lot of experience in finance and you know our organization inside out.”

I agreed, feeling an unaccustomed rush of enthusiasm. At seventy‑nine, I was starting a new career. Who would have thought it?

And then, exactly one year after that memorable evening when I showed Ezra the deed to the house, the phone rang. It was an unfamiliar number with a Portland area code.

“Abigail Tmaine speaking,” I said.

“Mom, it’s me.” Ezra’s voice sounded strange, muffled, almost timid.

“Hello, Ezra. I haven’t heard from you in a while.”

“Yeah, I… I should have called sooner.” There was a pause. I waited, not helping him. “Mom, I’m in trouble. Ivette left me.”

I felt no surprise or gloating—only a slight sadness for my son, who was facing disappointment again.

“I’m sorry, Ezra.”

“Things didn’t work out the way we planned. The job didn’t turn out to be as promising. The house we bought needs constant repairs, and Ivette’s parents—” He chuckled bitterly. “Ivette’s parents have not been able to help us as promised. Ivette’s father has serious financial problems. He invested all their savings in some dubious scheme and lost almost everything.”

“That’s how it is,” I said neutrally.

“Yes. And when it became clear that they weren’t going to be able to help us with the house repairs, Ivette changed—got irritable, started blaming me for everything. Said I wasn’t ambitious enough, that I was the reason she was stuck in this god‑forsaken town with perpetual rain. And then— then she met someone else, some manager at the firm where she got a job.”

I was silent, letting him talk.

“Three weeks ago, she packed up and left. Said she was going to file for divorce, that I… that I wasn’t good enough for her.”

I could hear such pain in his voice that my heart clenched despite all the hurt from the past year.

“I’m sorry, Ezra,” I repeated sincerely.

“You know what the ironic thing is? Her parents—those perfect Bingtons—turned out to be not so perfect at all. Ivette’s father, it turns out, has been scamming customers at his insurance company for years. He’s under investigation. And the mother— the mother always knew about it and covered for him. And yet they kept acting like a model family, teaching everyone how to live right.”

He was quiet for a moment, then added more quietly:

“I was such a fool, Mother. I compared you to them, always not in your favor. And you— you were always honest. Strict, yes. Demanding, but honest. You never pretended to be someone you weren’t.”

Those words I’d waited so many years to hear now sounded bittersweet. Too late. Too much water had passed.

“Thank you, Ezra,” I said simply.

“Mom, I’m thinking of going back to Carson City. There’s nothing else for me to do here. Everything is familiar there. I could go back to my old job— Bill Thompson hinted he’d take me back. And you and me, maybe we could—”

He didn’t finish the sentence, and I felt him waiting for an invitation from me. Permission to return not only to the city, but to my life. A year ago, I would have grabbed this opportunity with both hands. But now I was a different person—a person who had learned to value herself, her independence, her peace.

“Carson City is a beautiful city, Ezra,” I said softly. “And I think you’d really be better off here than in Portland. But if you go back, you’ll have to find your own place. I can’t offer you a place to stay with me.”

“I understand.” His voice sounded disappointed, but not surprised. “I didn’t expect you to welcome me with open arms after everything that’s happened.”

“It’s not about past hurts, Ezra. It’s just that I have a different life now. I work for a foundation. I have responsibilities, my own regimen. And I’ve learned to value my independence.”

“Yeah. Hope tells me you’re working now. That’s great, Mom.”

“Thanks.”

There was a pause. We both didn’t know what else to say.

“So… do you mind if I go back to town?” he finally asked.

“Of course I don’t. It’s your hometown, and we could see each other sometimes—have lunch together, maybe.”

“I’d like that.” There was hope in his voice.

“Me, too, Ezra,” I said. And it was true. I was ready for a new relationship with my son—a relationship between equal adults, not between a mother forever seeking approval and a son forever comparing her to others.

When we finished talking, I went out into the garden and sat on a bench under an old apple tree that Wallace and I had planted the year Ezra was born. It was a warm summer evening. The sun was setting, coloring the sky shades of pink and gold. I thought about the past year, about all the changes that had taken place in my life, about the work at the foundation that brought me fulfillment, about the new friends I had made among the volunteers and mentees, about Hope—who had blossomed into a more independent and confident person—and about myself. A woman who at seventy‑nine found the strength to start a new life. Who learned to appreciate herself without constantly comparing herself to someone else. Who finally realized that being herself isn’t worse or better than being someone else; it’s just the only way to be truly happy.

Ezra will come back to town, and we’ll probably build a new relationship. Or not build one. That would be okay, too. I no longer made my happiness contingent on my son’s approval—or anyone else’s.

The sun dipped below the horizon, coloring the sky a deep lilac. I rose from the bench and walked to the house—the house that now belonged to the foundation, but was still my sanctuary, my space, my private world. I was no longer afraid of the future. Whatever it would bring, I was ready to face it with an open heart and a clear mind. No regrets of the past, no fear of the future. Just as Abigail Tmaine—with all my flaws and virtues, with all my history, with all my strength.