My name is Savannah Ross, and for most of my life, the Whitaker family taught me exactly where to sit—just outside the kitchen door, at the auxiliary card table with the toddlers, the nanny, and the paper tablecloth that tore when you pressed your fork too hard. I learned how power arranges chairs. I learned how silence becomes furniture.

I am twenty‑nine years old and a public librarian in Denver. The Riverbend branch smells like old paper and lemon cleaner and the kind of hope that comes from laminated library cards. At dawn I make coffee in the cramped staff room; after closing I stay to file grant applications for the Open Page Collective, the literacy nonprofit I co‑founded with three friends in a basement office that floods every spring. We teach adults to read their world: lease agreements, job applications, custody paperwork, prescriptions. It’s not glamorous. It’s the work I was built for.

My father, Graham Whitaker, calls it a hobby.

He never calls me.

The text came in on a Wednesday afternoon while I was shelving new arrivals in American history. HARLON WHITAKER flashed on my screen—a name I had not seen in eight years, not since my grandfather sold his oil fields, took a buyout, and became the ghost that haunts every family portrait in our winter lodge. His message was six words: Come to Summit Crest for Thanksgiving.

I stared at the display until the words blurred. I typed back one word—Why?—and braced for nothing. Instead the three dots bubbled; a second message landed: For a private talk. Just us. Then a third: Bring the wooden box from your grandmother’s shed in Denver. Brass lock. Do not open it.

My grandmother, Eleanor Terrace, died before I was born. She exists in our house like a draft—felt, rarely named. The Denver property was hers before Whitaker money annexed every inch of our lives. The shed, I remembered, was damp and crowded with rusted tools that smelled like rain.

That night I found the key still hanging on the same nail by my mother’s back door. The shed yawned open on hinges that complained. I dug through tarps until my fingers found carved wood: a dark teak box the size of a shoebox, etched with vines, the brass lock cool and stubborn under my thumb. I carried it home and set it on my kitchen table. I did not search for a key. I did not cheat. I am a librarian; I respect a seal.

On my way to bed a stack of old photo albums slid to the floor. A single photograph skated free. In it I am six years old on the stone steps of the Summit Crest library, a gap‑toothed kid reading from a fat illustrated Odyssey. Beside me sits my grandfather, not the headline patriarch but a man leaning forward to listen. His expression is not pride. It’s attention—the kind that says, Go on.

In the morning my father called. He didn’t say hello.

“Your mother tells me you were sniffing around the shed,” he said, each word clipped like he was cutting coupons out of patience. “I hope you’re not thinking of indulging whatever fantasy that old man is peddling.”

“He invited me,” I said.

A humorless laugh. “Of course he did. He wants to embarrass me. Do not go. And if you insist on performing your identity crisis this week, do not bring anything he asks for. Not one thing.”

“Is that an order?” I asked.

“It’s protection,” he snapped. “For you. For us. This engagement is delicate.”

He meant my cousin Sierra’s engagement to a senator’s son. He meant press and donors and photographs with tasteful winter florals. He meant a dynasty with edges buffed smooth.

“Dad,” I said carefully. “What is Summit Crest if not a place to read?”

“The main table is for family, Savannah,” he said, and hung up.

I packed anyway. Heavy sweaters. Wool socks. My best boots. I slid my portable document scanner and the Open Page five‑year plan under the clothes. I wrapped the wooden box in my warmest scarf and tucked it like a heart into the center of the suitcase.

The road to Aspen cut through sky‑bright cold. At the private gate the guard checked my name, blinked at the car, swallowed his surprise at the 2011 Subaru with the cracked windshield and the bumper sticker that said LITERACY IS A CIVIL RIGHT. The driveway was a line of black Range Rovers and a green Bentley that looked as if it had opinions about the weather. Summit Crest rose from the mountain in glass and timber like a cathedral designed by a man who wanted to impress God.

Inside smelled like pine and money. The great hall lifted three stories; firelight licked a stone hearth as tall as a room. Portraits watched from the opposite wall—Whitakers back to the nineteenth century in oil and certainty. My father stared down at the world from gilt. Aunt Maxine glittered beside him like a winter knife. And at the beginning: Harlon young with clean angles, his jaw a threat, and next to him a dark‑haired woman with intelligent eyes. The brass plaque under her portrait read simply MRS. HARLON WHITAKER. The nameplate was new and polished, the others old with patina. Someone had chosen to erase her name—Eleanor—and to shine the blankness.

“Miss Savannah,” said Mr. Doyle, the butler who has been fifty‑nine years old since I was nine. He appeared soundlessly, all angles and dignity. He took my coat without glancing at the frayed cuffs. His eyes flicked, just once, toward the scarf‑wrapped box in my hands, and returned to my face. “Welcome home.”

“Is he—?” I asked.

“In the library,” he said. “We moved his rooms to the ground floor study so he can hear pages turn at night.” He paused the smallest pause. “He asked that your box be placed in a position of prominence.”

He lifted it from my arms with unexpected reverence and set it squarely in the center of the fireplace mantle, as if a small wooden heart could command a room built to impress kings.

From the dining room I heard laughter like breaking glass.

Maxine swept in first in winter white. Sierra followed—a perfect Instagram of herself—then the senator’s son, all teeth and handshake. My father came last, wearing the face that looks better in magazines than in mirrors. The long dining table gleamed, twenty‑four places set with crystal and silver. Place cards waited in gold ink: GRAHAM WHITAKER. MAXINE ELLIS. THE HONORABLE MARCUS SLOAN. SIERRA WHITAKER.

There was no card for me.

Maxine placed a warm palm on my arm, her bracelets soft gold bells. “Savannah, darling,” she said, with the pity she saves for stains. “You’ll be more comfortable at the conservatory table. It’s a better fit.”

“Better for who?” I asked.

“Don’t be dramatic,” my father murmured without meeting my eyes. “We have press tonight.”

A man in a simple dark suit stepped forward. He had a lawyer’s stillness. “Mrs. Ellis,” he said. “Mr. Whitaker asked me to ensure Ms. Ross is seated properly.”

“Jonah,” Maxine said, her smile losing molecules. “You’re still here?”

“Until I’m not,” he said mildly. He turned to me. “Jonah Vale, counsel to Mr. Whitaker. Ms. Ross, your mobile literacy proposal is excellent.”

I blinked. “You know Open Page?”

Before he could answer, a voice rolled across the stone like old whiskey poured thin. “She sits with me.”

My grandfather stood in the doorway with a plain wooden cane. He had thinned but not diminished. His eyes were winter bright. He crossed the hall slow and deliberate, fixed on my face as if the rest of them were ghosts. He stopped in front of me and opened his arms.

“You came,” he said.

I stepped into his embrace; he smelled like clean wool and old paper. For one moment I was the child on the library steps and he was the man asking, Can you read this one? Then he let go, turned, and—without raising his voice—rearranged the gravity in the room.

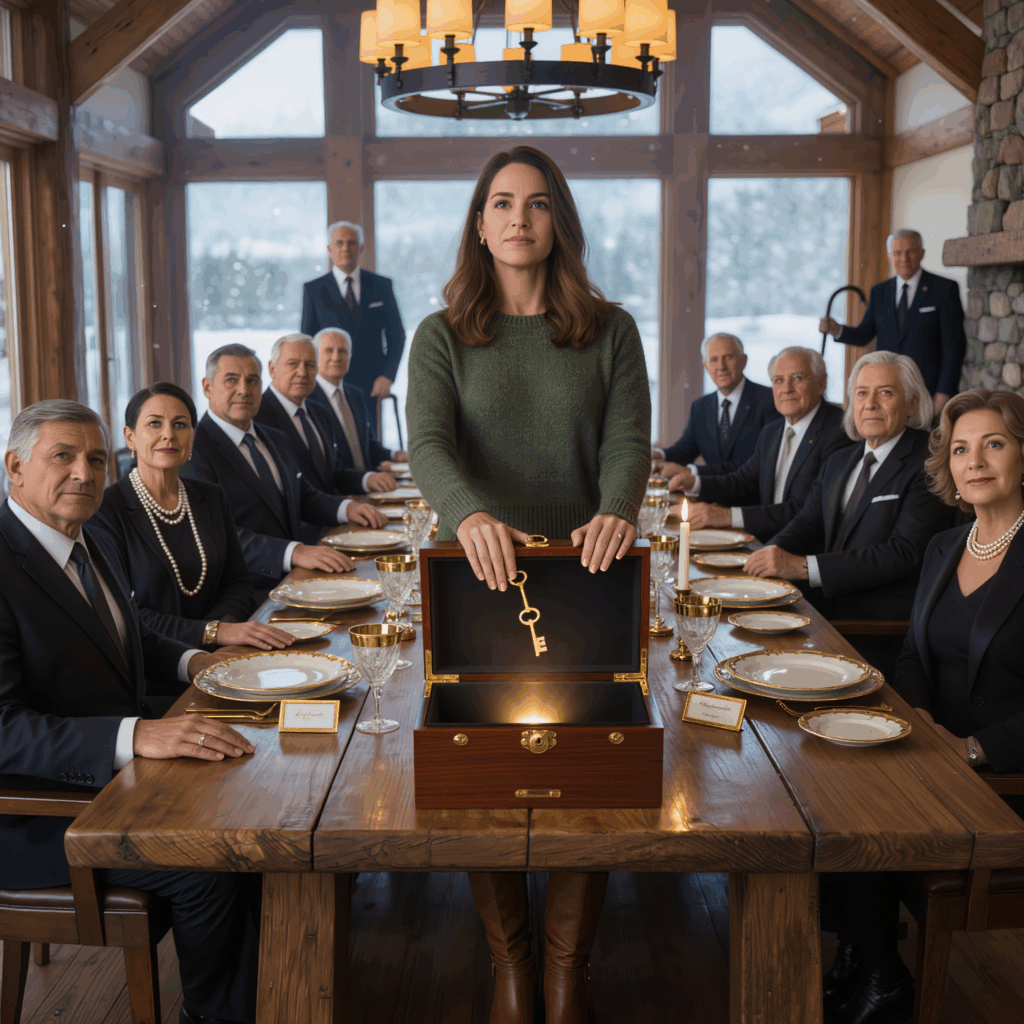

“There’s been a change,” he said. He plucked Maxine’s place card from the head of the table, considered it, then carried it to the back where a smaller table waited by glass and ferns. He set it down. “Maxine, the conservatory will suit you. Marcus, you’ll sit by your fiancée.” He walked back with the slow confidence of a man who still owned the floor and pulled out the head chair—the one carved like a throne—for me.

My father found words. “This is a celebration,” he said, voice ragged. “You can’t—”

“I can,” Harlon said simply. “My house. My table.”

Mr. Doyle placed a new setting in front of me with quiet ceremony. The room’s sound thinned to the ringing of crystal and the small knife of Sierra’s inhale. Marcus half laughed as if to make it camaraderie. “Sir,” he said. “Are we being punished for tardiness?”

“We’re being educated,” my grandfather said. “And tonight our lesson has a text.” He nodded once. Mr. Doyle lifted the wooden box from the mantle and set it in front of my plate. The tarnished lock threw a dull wink in the firelight.

My father sighed like steam. “Honestly, Father. Props?”

“Traditions,” Harlon said. He rose, walked the long length of the table with a gait that made his cane a metronome, and stopped at my shoulder. He didn’t whisper, but only I could hear him. “This is for Eleanor,” he murmured, and pressed a small brass key into my palm. The head of the key was etched with two letters: ET.

My fingers shook. The key slid in stubborn and then gave with a deep, satisfying click that sounded like a courtroom after a verdict. The lid lifted on a breath of lavender and paper and time. Inside lay three green leather notebooks, a bundle of ribbon‑tied letters, and at the bottom a heavy blue‑black volume embossed in gold: WHITAKER FAMILY CHARTER. ORIGINAL, 1979.

I looked up. Maxine had gone still. My father stared at nothing that looked like water.

I drew out the top notebook. My grandmother’s hand marched across cream pages in a script that was practical and beautiful. Lists of garden expenses. Notes about staff. Then, across a single page, calculations and a title underlined twice: THE TERRACE FUND. 10% WHITAKER EQUITY DESIGNATED IN PERPETUITY. PURPOSE: LITERACY IN COMMUNITIES AFFECTED BY OUR OPERATIONS. ANNUAL PUBLIC REPORT EACH NOVEMBER.

Ten percent. Not a rounding error. The moral engine.

I flipped again and a black‑and‑white photograph dropped into my lap. Eleanor—not pearls and pearls but rolled sleeves and chalk dust—stood at a blackboard in a cinderblock hall, oil workers seated with books open like passports. On the back: WYOMING, 1982.

“Savannah,” my grandfather said, not looking away from my father. “Read.”

“What would you like me to read?”

“Anything,” he said. “Her words.”

So I read. I chose a page at random. I found a section titled BYLAWS OF RESIDENCE, SECTION 4. ON THE RIGHT TO A SEAT AT THE MAIN TABLE.

“It is mandated,” I read, my voice steadying into the room‑filling cadence I use for story time and bond hearings, “that a seat at the main table be held for any member of the Whitaker line, direct or by marriage, who engages in intellectual work and service to the community. This shall include but not be limited to education, literacy, the sciences, and the arts. This seat is non‑transferable and holds precedence.”

Silence snapped taut. Across the table the senator’s son smirked without understanding; Sierra’s eyes shone like glass over water. My father’s jaw clicked.

“An archaic clause,” he said too loudly. “Irrelevant.”

Jonah pressed a small remote. The far wall—a dark panel I had assumed was art—woke as a screen. On the left: Whitaker Family Charter, 1979, the very text under my hand. On the right: Whitaker Family Charter, 2004 Revision. Jonah highlighted Section 4. The language on the right said only: SEATING AT FAMILY FUNCTIONS SHALL BE AT THE SOLE DISCRETION OF THE BOARD.

“Housekeeping,” my father said. “Legal modernization.”

“Erasure,” Jonah said, mild as winter sun. He clicked again. “Section 9. The Terrace Fund.” The 1979 text glowed: 10% equity. Perpetuity. Annual public report. On the right, the 2004 clause was one sentence that hit like a plow. ALL SUBSIDIARY FUNDS, TRUSTS, AND CHARITABLE DESIGNATIONS, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE TERRACE FUND (DEFUNCT), ARE HEREBY DISSOLVED…

“Defunct,” I heard myself say.

Maxine smiled with her teeth. “Reallocated,” she corrected. “The market moves. We adjusted. The family has larger responsibilities than sentimental line items.”

“Then where did the money go?” I asked. My voice came out calm, a librarian asking for a call number.

Jonah clicked once more. A flowchart appeared—simple boxes, brutal arrows. WHITAKER RENEWABLES DIVIDEND POOL → 10% EQUITY DIVIDEND → BLUE ASH HOLDINGS, LLC.

I knew that name. I had seen it once in the corner of a discarded spreadsheet my father had left at my mother’s house years ago. Blue Ash Holdings felt like a lie that had gotten comfortable.

“The vehicle was formed in Delaware three days after the 2004 revision,” Jonah said. “Private. Unlisted. Two signatories.” He clicked: GRAHAM WHITAKER. MAXINE ELLIS.

Sierra made a tiny noise, white‑hot with betrayal. Marcus pressed her knee under the table like a handler. I watched him thumb a text beneath his napkin and saw the reflection of his message in his water glass: a tabloid logo in holiday colors.

The room stilled the way rooms do before someone finishes a long, slow fall. Jonah’s next slide was a circle pieced into colors that meant money gone: nightclubs; a penthouse in Vail; equestrian imports labeled “operating losses”; a sliver marked “money market (liquid)” as if to prove the joke could do math.

My father surged to his feet. “This is privileged communication,” he barked. “You’re fired.”

“You can’t fire me,” Jonah said pleasantly. “I don’t work for you.” He set the remote down and folded his hands. “We will discuss privilege in discovery.”

Discovery arrived early. The CFO, a pale man with a permanent flinch, stood, walked the length of the table, and placed a silver USB drive beside Jonah’s elbow with the careful reverence of a man handing over a detonator. “My resignation,” he said hoarsely, “and a complete record. It’s already with the SEC.”

Maxine’s clutch fell open; a hotel key card slid out and landed face‑up on the rug. SOLARIS VAIL. PENTHOUSE C. For once, she had no performance to give.

Harlon’s cane cracked against stone. “Enough,” he said. “We will take dessert in the library.”

We did not take dessert. We took judgment.

In the library the air smelled like leather and winter. Harlon went behind the desk that had anchored a hundred decisions. Jonah stood at his shoulder with the USB drive and a neat stack of papers. My father and Maxine remained standing on the Persian rug as if chairs had become treacherous. Sierra crumpled onto an ottoman, mascara like ash down her wrists. Marcus lingered by a bookcase calculating exits.

“The box isn’t empty,” Harlon said, nodding to the wooden heart I had set on a reading table. “There’s a letter with your name on it.”

The envelope was thick, cream, sealed with red wax pressed ET. My grandmother’s script on the front: To the grandchild who keeps the word. I broke the seal with my thumb and read aloud because when the room is full of people who only know how to sign their names, reading out loud is a revolution.

My dearest Harlon, and my dearest grandchild, the one who keeps the word…

She wrote about Wyoming men who could drill but couldn’t read warning labels; she wrote about promises made in this very room; she wrote that the Terrace Fund was not a write‑off but a vow; she wrote that someday our children would worship the index and call literacy a hobby; she wrote my name.

I finished with my voice clear and lower than my usual. It felt like standing on bedrock.

“I accept,” I said.

My father laughed, a brittle sound. “Absolutely not. This isn’t succession by story hour.”

“It isn’t,” Jonah agreed. He slid a document across the desk. “It’s succession by law. The fund was never dissolved—only raided. This transfers signatory authority and administrative control of the Terrace Fund and its assets to the ranking family member who meets Section 4 criteria.” He looked at me. “That would be the librarian.”

Harlon uncapped a heavy pen. He signed. Maxine lunged—pure instinct. Mr. Doyle materialized and caught her wrist with the inexorable grace of gravity. Jonah slipped the signed document into an envelope. Somewhere inside me a door that had always been locked softly opened.

Sierra rose on shaking legs. “I tried to fix it,” she blurted. “Last night. I followed the CFO. I searched the window benches for—” Her eyes flicked to the mantle in the hall as if she could see through walls. “For the box. I wanted to be…real.”

She broke. Not performative tears—small, ugly, human ones. I believed her because wanting to be real in a family that loves optics more than oxygen is the most comprehensible sin in America.

Jonah slid the USB into the desk hub. The screen filled with emails and spreadsheets and six years of line items labeled as communications when they were hush money and liquidity when they were a mortgage on a nightclub dream. He read only what mattered. When he finished, Harlon lifted his eyes and said the words that end kingdoms: “We will be making a public statement.”

Graham went wax white. Maxine’s smile lost anchor. Mr. Doyle’s voice appeared on the intercom: “Sir, the press is at the gate.” Of course they were. When the cameras arrived, we did not hide.

The great hall became a press room. The wooden box sat on the mantle like a judge. Harlon spoke first—not for long. He identified the theft and announced restitution. Then he handed me the lectern. I spoke about the fund’s purpose and the plan—mobile literacy centers; night classes with unions and colleges; an app we built with volunteer coders to deliver adult literacy discreetly and free. I named our partners in Wyoming and New Mexico and Colorado and the metrics by which I would insist on being judged. I did not sell contrition. I sold work.

A Denver reporter asked how a librarian could manage a multi‑hundred‑million‑dollar fund.

“By spending it with precision,” I said, and put our two‑year rollout on the screen. “The fund does not need a hedge fund manager. It needs an educator with a budget and a spine.”

Marcus tried one last spin, but Jonah lifted his phone and read the tabloid text Marcus had already sent. A camera turned to catch Sierra sliding off her ring and placing it gently at his feet. “Go sell that,” she said calmly. “It’s the last cent you’ll get from us.”

Harlon suspended my father and Maxine from their governing seats pending audit and clawback. The crowd inhaled like one body. I felt the ground shift—then settle.

When the lights died down and the press began to pack, Harlon turned to me with a look I didn’t recognize on his face. Not pride. Relief. “There is one more letter,” he said softly. From the very bottom of the box he pulled an envelope the color of dried blood. For Harlon, it read, to be opened the day you realize who truly holds this house.

His hands shook as he broke the seal. He read silently, and grief moved through his face like weather. He lifted the page. At the bottom a thin notarized strip had been tipped and glued in 1979.

“She left a fail‑safe,” he said hoarsely. “A moral invocation attached to the corporate will. If the charter is willfully breached and that breach is declared publicly by the head of the family, then all dividends from all Whitaker equity—not just the ten percent—shall be diverted to the Terrace Fund for twenty‑four months.” He looked at me. “Activated upon request of the grandchild who keeps the word.”

Jonah read it three times. “Ironclad,” he said, and exhaled like a man watching a bridge hold.

My father made a sound that was not language. Maxine stared at the floor as if the wood might open and swallow her. I thought of the Wyoming hall in the photograph and the way Eleanor pointed at a blackboard like a general pointing at a map.

“Activate it,” I said.

Harlon nodded once. We faced the lone camera still live in the corner; he raised our clasped hands like a referee after a decision. “Today,” he said, voice ringing under timber and glass, “we activate the clause.”

A silence fell that felt like snow—soft, absolute, and changing everything it touched.

Work began immediately. Jonah and the auditors took over the conference room. Mr. Doyle re‑directed the staff into a war‑room of coffee and sandwiches and charging cables. My phone vibrated in a steady pulse: volunteers, donors, community colleges, union reps, friends who had seen the feed and were ready to drive buses through the night.

In the middle of the rearranged world, a small thing happened that I will keep when I have forgotten the rest: my mother, Nora, slipped in at the edge of the hall like a shadow that had learned to walk. She stared at the head of the table like it was a cliff.

“Mom,” I said, pointing to the empty chair beside me. “Please.”

She came forward the way you approach a skittish animal. She sat. She cried in that silent way that is more air than sound. I put my hand over hers. She squeezed once, bone and gratitude, and looked at me as if I had just found our way out of a maze.

Sierra moved to my side. “I can’t read contracts,” she said, voice raw. “But I can plan logistics. Your route map won’t survive a Colorado winter. I’ll be your field coordinator for Wyoming. I need a real job.”

“Volunteer contract,” I said. “One year. We’ll pay a living stipend when the fund clears. Training starts Monday.”

She nodded like someone stepping into cold water because the river is the only way home.

That night, after the auditors sealed the conference room and the press vans bled tail lights into snow, Harlon called the remaining family to the great hall. He held up a heavy antique serving spoon, its handle engraved with a single elegant T. “The gratitude spoon,” he said. “Only tradition worth keeping. The head of the table leads the thanks.” He set it in my palm. “You’re the head,” he said without ceremony.

I stood. The room that had been a stage for humiliation was now full of staff and cousins who looked shell‑shocked and human. “I’m thankful for everyone who’s ever been shoved to the auxiliary table,” I said. “I’m thankful you waited for us this long.”

The staff clapped first—Mr. Doyle, the cooks, the valet who had moved my Subaru away from the Bentleys like a kindness. Then others joined until the sound filled the rafters. I did not cry. Not then.

The next days were a flood. Lawyers flooded. Auditors flooded. Money, for once, flowed in the correct direction. We opened accounts with structures Jonah described as “belt, suspenders, and a seat belt.” The fail‑safe clause moved dividends like a river rerouted, and for the first time in family history the current went where the charter said it should.

I rented an office for Open Page with windows that saw daylight. We bought our first bus—secondhand, stubborn, beautiful. Sierra tore up my original route plan with a red pen and taught me how to read a Wyoming winter. Maria, one of our graduates, passed her RN exam and cried in the lobby of the testing center; Robert fixed our building’s aging HVAC with a certification he’d earned six months earlier in a class I’d taught.

On December twenty‑third we parked Bus One in a windswept lot behind a union hall in a town my father had never learned to pronounce. We strung warm lights along the roofline and opened the doors. Adults climbed the steps with embarrassment and left two hours later with library cards and appointments and a smile you can’t fake. At ten p.m. a woman in a housekeeping uniform came in straight from a motel shift and whispered that she wanted to learn to read a bedtime story to her daughter on Christmas Eve. We found a book with a blue dog and a stubborn rhyme; we practiced until her voice stopped shaking; we printed a certificate with her name and the date and a gold star she insisted was for her daughter and not for herself.

I called my grandfather from the back of the bus. He answered on the second ring.

“How many chairs?” he asked without hello.

“Forty tonight,” I said. “More tomorrow.”

He inhaled quietly, the way a man breathes when pain loosens its fingers. “Your grandmother would have liked those lights,” he said. “She’d have told you to buy two more strings.”

“I already did,” I said, and he laughed, a small, new sound.

On Christmas morning Mr. Doyle drove my mother up to the union hall in a black SUV that looked lost in the gravel. He stepped into the cold in his thin shoes and carried a paper bag like an heirloom. Inside were ginger cookies and the gratitude spoon wrapped in a cloth napkin. “A loan for the day,” he said, placing it in my hand. “From the house that finally learned what it’s for.”

We held a pot of coffee over a camping stove and passed out cookies wrapped in paper. The woman from the motel came back with her daughter. She read the blue dog book, halting then strong, in a voice that made strangers weep. When she finished the little girl clapped like a storm of birds.

That afternoon Sierra texted me a photo of the penthouse key card snapped clean in two. Under it, her caption: RETURN TO SENDER. She had signed her volunteer contract and was already on a bus listserv terrorizing the drivers in the best way. Marcus posted an apology that sounded like an intern wrote it and then vanished from our feeds.

In January Reuters ran a headline that should have been impossible in our family: STOCK DIPS, THEN RALLIES AS WHITAKER FAMILY ANNOUNCES AUDIT, RESTITUTION, AND LITERACY FUND OVERSIGHT. Small shareholders—people who had never set foot in Summit Crest and never would—sent me emails thanking me for saving a thing they owned with their tiny pieces of hope.

In March, at our first Terrace Fund board meeting conducted with the kind of sunlight that scares liars, we adopted a rule that could fit on a napkin: If you don’t set an extra chair for the person at the door, you don’t sit. Jonah had it inscribed on a plaque and hung it in the conference room at eye level. No one argues with eye level.

In May my father sent a letter, not an email. He said he’d entered treatment and wanted to make amends. He said words that sounded right and felt untested. I mailed him a schedule of the bus routes with a note in my neat librarian print: Open seat on Fridays. No press. Just work. He did not come. Not that week.

In August he did. He arrived in a plain jacket without a photographer and asked if he could help carry boxes. We put him on table duty—assembling folding legs that pinch if you’re careless. He bled once, swore softly, apologized. He poured coffee for a man in a hard hat and didn’t correct the man when he mispronounced Whitaker. I watched him learn to be useful in a room where his name meant nothing. He went home tired and very quiet. He came back the next Friday with cookies he said he made himself and that, miraculously, did not taste like penance.

The thing about justice is that it is loud at first and then becomes a rhythm. We built buses and hired tutors and sat with men who signed their name with an X because a foreman told them that’s what counted. We sat with women who had hidden their inability to read from their children the way you hide a bruise you love too much to admit is there. We watched eyes widen at the first paragraph read without help. We learned the names of dogs tied outside during night class. We fixed a busted heater with Robert and rolled out a pilot of our app that blinked and stalled like all new things and then finally ran.

On the first anniversary of the night the table flipped, we held a dinner at Summit Crest not for donors or press but for the bus drivers, tutors, and graduates who wanted to see where the spoon came from. We moved the long table to the side and rolled the buses’ folding tables in. We set mismatched plates and used paper napkins without apology. Mr. Doyle hovered near the kitchen with a look that said he was allowing this not because it met standards but because it met the moment.

Harlon stood beside me at the mantle. He seemed smaller and somehow larger—like stones look bigger in streams than in fields. He tapped his cane once for silence and said what he had learned to say: “The head of the table leads the thanks.” He handed me the spoon.

I did not give a speech. I lifted the spoon like a gavel and pointed at chairs until every seat was filled, even the folding ones against the wall. Then I pointed at the door and made my father carry in three more from the mudroom because tradition without muscle is just nostalgia.

We ate too much. Sierra made a slideshow of routes that made the bus drivers hoot and sink in their seats from pride. Maria stood and said she’d passed her RN and that the first thing she’d done with the raise was buy a bookshelf. Robert told a joke so old it came back around to new. My mother sat next to Harlon, and they argued cheerfully about whether a library should smell like dust or lemon oil.

When coffee cooled and plates were streaked with pie, I stood and held the spoon one last time for the night.

“They never let me sit at the table,” I said to the room that had once believed that was wisdom. “But we don’t live in that house anymore.” I looked at the faces: staff, graduates, cousins who had stayed to do the work, a grandfather who had finally figured out what wealth is for. “If you ever find yourself standing while there’s room to sit, you have my permission to make space. Move a chair. Bring one in from the mudroom. Take the head seat only long enough to give it away.”

After the laughter and the clatter, after the hall emptied down to echoes and crumbs, I carried the wooden box back to the library. I set it on the reading table in the pool of late light and opened it. The notebooks smelled like time and intention. I touched the first page of the first notebook and wrote in the margin with a pencil so soft the mark looked like breath: We kept the word.

As I closed the lid, footsteps creaked in the doorway. My father stood there with his hands in his pockets like a teenager caught where he wasn’t supposed to be.

“Do you need help with the chairs?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “Take the conservatory. There’s always one more.”

We folded tables side by side. He carried two at once because stubbornness is a kind of love in men who don’t know how to say it. When we finished, he stood looking at the empty hall as if trying to calculate what was missing and what had been restored.

“You were right,” he said finally. “Not about everything. But about the table.”

“I know,” I said. “That’s why we built more.”

We turned out the lights. The glass reflected a hundred small squares of night. Somewhere below, in the valley, a bus idled and then purred forward, carrying its cargo of chairs into towns that had learned to expect little and were slowly learning to accept enough.

At the door my grandfather waited with his cane and his old, bright eyes. He looked at my father and then at me and then at the empty room that had, for once, been used correctly.

“Come on,” he said. “The pages won’t turn themselves.”

We walked back to the library together and opened the box again, not because we needed to—because it felt good to see what a promise looks like on paper. Then we began the thing we were made for. We read.

In the weeks after New Year’s, the audit bared its teeth. Numbers that had once lived as rumors learned to walk in daylight. The team Jonah assembled moved like a search party with lamps high, their questions short and unafraid. When they found an answer that flinched, they followed it into the brush until it stopped running. I sat through most of it because stewardship is not a line item—it’s a presence. Sierra sat through all of it because logistics is how she says I’m sorry.

On a Tuesday that smelled like snow, the SEC requested interviews. On Wednesday, small shareholders packed a webinar and asked better questions than the board ever had. On Thursday, Mr. Doyle set extra mugs on the conference table and, without being asked, placed a plate of ginger cookies by the chair that used to belong to my father. He looked at me, one eyebrow a question. I nodded. Leave it. We were practicing the world we wanted.

Maxine did not practice. She hired a crisis PR firm whose emails sounded like a weather report in which the storm is always someone else’s fault. She posted a video filmed in flattering afternoon light in which she regretted, reaffirmed, recalibrated, repositioned, and did not apologize. The comments, for once, taught her something she could not curate: when you steal from the word, the word eventually speaks back.

The fail‑safe clause began to move capital like a tide. The first dividend cycle hit in February. Jonah called me into the conference room, where the monitors were a calm, blue ocean. He pointed to a transfer request that looked like a down payment on a country. “There,” he said, voice formal and also, I swear, a little giddy. “Press the button.”

I pressed it. The Terrace Fund account ticked forward. For a long minute, no one spoke. Then Mr. Doyle, who had absolutely no reason to be in the room except that he had learned where history sits, cleared his throat and said, “Tea?” and we all laughed because our bodies had to do something human.

We bought Bus Two in March and Bus Three in April. Robert flew out to examine engines with a quiet competence that made salesmen less loud. We learned the art of used tires and the science of warm air across cold floors. Sierra built a bulletin board out of a sheet of plywood and string and pinned maps with yarn like a detective, except the crime was illiteracy and the suspects were every zip code no one ever funded. She named each bus not for a donor but for a librarian who had kept a town alive. When the vinyl arrived, Mr. Doyle insisted on peeling the backing himself, hands steady, breath held. He smoothed the letters with his palm like a blessing.

The first spring storm blew slantwise across Wyoming the day we piloted night classes at the union hall. We taped ‘OPEN’ to the bus window. The sign flapped and knocked like a persistent neighbor. Men walked in smelling of diesel and wind. Women came in with their breath tight as ropes. We began with names, then addresses, then the kind of form that has always been a gate: W‑4s, job applications, rental agreements. No one failed. Not one single person failed in that bus, because failure requires permission and we did not give it.

I kept a notebook of small victories because big victories make headlines and then depart. The small ones stay. A grandmother reading the back of a cereal box to a boy in a Spider‑Man shirt. A roofer filling out a bid form without needing to ask his teenage daughter to translate the math. A sheriff standing in the doorway and choosing to drink his coffee outside instead of looking over shoulders. Sierra catching a black ice warning on a county Facebook group and rerouting two buses at 5 a.m. A man in his late fifties taking the pre‑test five times in a row, then on the sixth attempt closing his eyes, inhaling, and reading the first paragraph aloud as if laying down a brick he could stand on.

My father came on a Friday and did not come on the next. He came on the Friday after that with a thermos of coffee and a bad joke about folding chairs. He stayed to help tear down. He asked one of our tutors whether he could sit in on a session the following week “just to listen.” On the drive back to Denver he texted me a photo of the sky at dusk and wrote, simply, It’s quieter out here. I did not know if he meant the wind, the mind, or the noise he had once needed to survive himself. Maybe all three.

Maxine fought. She hired lawyers whose suits cost more than a bus and whose sentences took three clauses to say no. Jonah met them with patience sharp enough to cut. The audit did not care for theater. It cared for numbers. By summer, clawbacks began. I signed papers with my name that returned money to a promise my grandmother wrote before I took my first breath. Each signature felt like planting a fence post and saying, This line doesn’t move again.

Harlon watched the seasons through the glass like a man watching a play he had paid too much to miss. Some mornings he was brittle, others bright. He listened to me read grant proposals out loud as if the meter mattered, and—God help me—it did. When he tired, he asked me to leave the library door open so he could hear pages from the hall. He taught me how to do nothing with grace for twenty minutes at a time. He began telling stories that had slept in his bones—the roughnecks who pressed paychecks into callused pockets, the town diner that would not serve his foreman until Eleanor walked in and took the head booth, the way a woman with chalk on her hands convinced a hard country to admit it needed a teacher.

In August the senator’s office requested a meeting. Sierra said she’d handle it and I believed her. She showed up in a navy blazer and boots that could walk through a blizzard. She took a folder labeled ROUTE PERMITS and, without ever raising her voice, taught a junior staffer the difference between obstruction and assistance. She left with a permit signed and a promise I trusted because it lived in writing and because we now had lawyers who collected promises like firewood.

One evening in early fall, after a long day of intake at the bus, I drove alone up to Summit Crest. The road climbed through aspen that shivered like coins. Inside, the great hall was quieter than I liked. The mantle was empty. The box was in the library, open, because pages should breathe. I found Harlon in his chair by the window. He was looking at the far peaks with an expression I had learned meant the past had caught him.

“Savannah,” he said, without turning. “I have been trying to remember the first time I sat at a table where I didn’t belong.”

“Did you leave?” I asked.

“I learned to stay,” he said. “And then I built a bigger table. And then I forgot why.” He tapped the arm of the chair with two fingers, a restless cadence. “If you ever forget why, box my ears. Promise me.”

“I promise,” I said.

He smiled at the glass. “Good,” he said. “Because you’ll need the speed.”

He died in late October with his hand on a book. Mr. Doyle called me; I drove up in the first dark and sat with him while the house remembered how to be a home. We held a service in the library and read the first paragraph of the charter out loud. We placed the gratitude spoon on top of the box because some objects deserve to be companions. When the official mourners left and the unofficial ones stayed, we ate stew from bowls that didn’t match and told stories about a man who had learned, at the end, to listen.

I inherited nothing except the duty already in my hands, which felt like wealth enough. My father stood at the edge of the room like a boy and then, after everyone else had gone, he asked if the library needed anything. “A rug,” I said. “Winter’s coming.” He went to town the next day and returned with a Persian that looked like it had witnessed dinners and arguments and late‑night reading. He laid it down without performing generosity. Mr. Doyle approved it with a noise that was almost a laugh.

November came back around like a book you’re ready to reread. We held our second Thanksgiving under glass, but this time no one arranged chairs without first checking for the extra. The press asked to attend. I said no and sent them photographs of hands turning pages and adults writing their names in ink that didn’t tremble. We set the head seat for the librarian on duty that week. It wasn’t me. It was a woman named Dee who runs our night intake and can talk a man who thinks he’s stupid into trying one more time.

At dessert, Sierra stood and asked for the room. Her voice carried without strain. “I did not understand what a seat costs,” she said. “I thought they were given with rings and press releases.” She took a breath. “I would like to earn one. I’m applying for the open operations lead role. My résumé is routes.” She looked at me without flinching. “If I’m not the best candidate, don’t hire me.”

“Show up Monday,” I said. “Interview’s the work.” She did, and did not let me down.

Winter laid a hand on the buses and dared them. We learned to plug in block heaters at dusk and to park with the nose out. We learned which tires will lie to you about their loyalty. We learned how to say we’ll be back tomorrow and then, even in sleet, make it true. The app passed one hundred thousand active learners—most of them anonymous, many of them using phones with cracked screens and thumbs that moved fast because life had taught them speed. We built an offline mode that worked in dead valleys by caching lessons like good secrets.

By spring of the second year, the clause’s two‑year clock had almost run. I woke some nights counting chairs like the old fable counts sheep. The money had moved. The buses had rolled. The classes had filled. And still the need was larger than any single family’s apology could fund. I began writing a plan titled AFTER THE CLAUSE in a folder no one else could see. It was full of the boring, beautiful things that keep promises alive: endowments with handcuffs, local revenue lines, community boards with teeth, data that proves the work so thoroughly even cynics get bored of doubting.

The last board meeting before the clause expired was held at a community college in Casper because sunlight belongs in rooms where students walk. The agenda was short. Jonah summarized the audit’s endgame and the legal reforms encoded into our bylaws. Sierra presented a winterization protocol that made three bus drivers fist‑bump in the back row. Dee rolled out a pilot for a prison reentry literacy course. Robert adjusted the thermostat, then, at my request, sat at the head of the table and led the thanks. He cleared his throat and said, “I’m grateful for the day Ms. Ross told me failure requires permission, and nobody here gives it,” and then he put his face in his hands for a second because men cry and the room did not break.

I stood last. I looked at the faces that had learned my name for more than scandal. “The clause did what it was built to do,” I said. “It bought us time to build something that doesn’t rely on the shame of two people.” I took a breath. “Tomorrow, the river returns to its banks. We will not beg. We will invoice. We will not apologize for needing fuel and tutors. We will present results and ask towns to join what they already built with us.”

I closed the folder titled AFTER THE CLAUSE and opened the one titled NOW. Work resumed.

The clause ended on a Tuesday with less drama than anyone would believe. The money went back where structures directed. The Terrace Fund, no longer the only artery, became what Eleanor had drafted: a heart that beats regardless of headlines. Donors who had once waited for funerals sent checks while still alive. Unions baked us into their training budgets. Counties cut line items not because of pity but because we were cheaper, better, and already parked behind the building with the lights on.

On the second anniversary of the night the box opened, we held a small ceremony in the library. We didn’t stream it. We didn’t invite press. We invited people who had turned pages with us. My mother baked a cake so lopsided it looked like honesty. Mr. Doyle wore a tie that predated me. Jonah left his phone in a drawer on purpose. Sierra brought a binder labeled YEAR THREE that made me almost as happy as cake.

I opened the box and placed inside it a new thing: a flash drive with the app’s open‑source code and a printed letter in my grandmother’s script, forged by time through my hand. It read: To whoever keeps the word after me. You do not need permission. You already have it.

My father arrived late. He did not make an entrance. He took a chair at the edge of the rug and, when I finished, raised a hand halfway. “I have something,” he said, looking at no one and everyone. He stood. “I spent two years learning how to carry tables,” he said. “It was harder than it sounds.” A nervous laugh rolled the room. He swallowed. “I’m not asking for a seat. I’m asking for a job.” He pulled a sheaf of paper from his jacket—printed notes, scribbles, a draft that looked like he had fought with it. “I’ve been writing in the mornings,” he said. “I think that’s called being a beginner.” He looked up. “I want to teach a class on reading contracts. Not the law. The common sense. The ‘don’t sign this clause, kid’ kind of class. You can put me in a church basement with a whiteboard. You can pay me or not. I’ll show up.”

Jonah coughed into his hand in a way I had come to recognize as a man who has just felt something in his chest. Dee nodded once, decisive. Sierra wrote Contract Literacy on a sticky note and stuck it to my sleeve. I looked at my father, who had built nothing and now wanted to build something small and true.

“Friday,” I said. “Seven p.m. Bring a whiteboard marker that works.”

He did. The class filled. He did not perform. He pointed at lines. He told stories on himself that made men grin and women make noises that meant, Yes, I’ve met that clause. He said the sentence I had learned to trust in him: “I don’t know.” He asked Jonah questions between sessions and took notes like a student. He did not become the man he imagined he once was. He became useful.

The year went on. We added a bus in New Mexico and a satellite office in Montana. We built a small scholarship with an ugly name—The Auxiliary Table Grant—because humor belongs in budgets too. We trained tutors in a church basement with acoustics that made even shy voices carry. We taught the app to read dialect, then to be patient. We learned that some days a person needs a warm room more than a worksheet and that some nights a worksheet saves a life because a job follows it.

One evening in late autumn, after a long day of enrollment and coffee and the thousand small fires any good work produces, I drove back up to Summit Crest. Snow had begun to fall the way it does in the mountains—quietly, like a decision. Inside, the great hall was full of the right kind of mess: folded tables leaned by the wall, a basket of scarves for anyone who forgot theirs, a stack of children’s books Maria had left “just in case.” The mantle held the wooden box and the gratitude spoon, side by side, as if on a mantel of a normal family that had earned its normal.

Sierra sat cross‑legged on the rug with route maps fanned around her. Dee slept in an armchair with a pen in her hand. Mr. Doyle dusted the top of a bookshelf and pretended not to listen to the world he had protected long enough for it to change. Jonah sat on the hearth stone, tie loosened, a rare smile on his face that said even lawyers like endings.

I walked to the box, not reverent now but familiar, and opened it for the thousandth time. The lavender was almost gone, replaced by the smell I like better—the clean paper scent of work in progress. The notebooks waited, and there was room for more. I took a blank one from the drawer, wrote the date, and then, under it, a sentence I have come to trust as the only ending worth writing:

We set another chair.

Outside, the buses sat under new snow like animals breathing in their sleep, ready to wake at dawn. Inside, we turned off lights one by one until only the library glowed. The house, at last, held the right kind of quiet—the kind made when pages turn and people listen. We left the door open so the sound could travel. We went on reading.