PART 1

At my wife Martha’s funeral, I stood alone in the rain. I am Walter, sixty‑seven years old, and I watched them lower her casket into the frozen ground at Mountain View Cemetery in Vancouver. The chapel had been empty—just me, a young minister who had never met Martha, and forty‑three years of memories sealed in a pine box.

I pulled out my phone—force of habit. No missed calls. No texts. I opened Instagram. There was my daughter, Amber, thirty‑eight, posing in front of a Christmas tree at a boutique hotel in Whistler. Designer ski jacket. Glass of champagne. The caption read: “Living my best life. Self‑care isn’t selfish.”

I swiped. There was my son, Ryan, forty‑two, shaking hands with a developer at a ribbon‑cutting ceremony in Toronto. That confident smile I used to be proud of. They chose photo ops. They chose networking events over their mother’s goodbye. They thought I was just a broken old firefighter—a relic from another era—someone to be managed and then forgotten. They had no idea what was waiting for them.

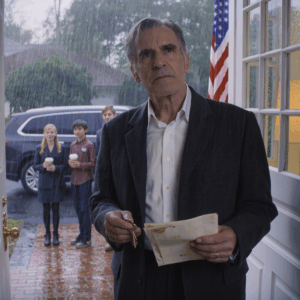

The next morning, when the doorbell rang at nine, I was sitting in the kitchen. I had been awake since four. The house was too quiet without her. I opened the door. There they were, Ryan and Amber. Not in black. Ryan wore a charcoal suit—expensive—the kind you wear to close a deal, not to mourn your mother. Amber had on cream‑colored athleisure—Lululemon, probably. Her hair was in a high ponytail. She looked like she had just finished a yoga class. They carried Tim Hortons cups and a paper bag with bagels.

“Morning, Dad,” Ryan said, walking past me like he owned the place. The smell of his cologne filled the hallway—too much of it.

“We brought breakfast,” Amber said, placing a large coffee in front of my usual spot at the kitchen table. “Double‑double. Just how you like it.”

That small gesture—that calculated kindness—sat in my stomach like a stone.

I sat down. This was Martha’s kitchen. It should have smelled like her cinnamon rolls and her laughter. Now it just smelled like lies.

Ryan took the chair across from me and cleared his throat.

“Listen, Dad. About yesterday, about the funeral… I am so, so sorry.”

I just looked at him.

“It was the closing on the Yonge Street development. Three years of work. Forty million dollars. I had to be there. You understand? I’m the principal developer. I couldn’t just walk away.”

He looked at me with Martha’s green eyes, but all the warmth was gone. The company—the one I had encouraged him to start, the one Martha and I had cosigned the first loan for—believing he would make something good.

“Mom would have understood,” he added, twisting the knife. “She was always practical about business.”

Amber, who had been checking her phone, finally looked up.

“And my event, Dad—it was huge. A brand partnership with a major wellness company. I had a contract. I couldn’t cancel. They would have sued me.”

Brand partnership. The words just hung there. I looked at my daughter. At thirty‑eight, she was a construct of filters and sponsorships. I remembered a six‑year‑old girl who cried for a week when our golden retriever died, who refused to go to school because she wanted to stay home and keep the dog’s collar under her pillow. Where did that girl go?

“It’s complicated,” Amber said. “You wouldn’t understand. It’s my work.”

I let the silence stretch.

“Anyway, I’m devastated,” she continued, sipping her coffee. “It happened so fast.”

So fast. Martha had fought heart disease for nine months: hospital visits, medication adjustments, the slow loss of strength. Nine months where I held her hand every single day. Nine months where Ryan was too busy with developments and Amber had a sponsored retreat she just couldn’t miss.

“We sent flowers,” Ryan cut in. “A huge arrangement. Very tasteful.”

I remembered the flowers. They had arrived at the funeral home with a card that said “From Ryan and Amber Miller.” They hadn’t even bothered to write it themselves. It was printed.

“Dad, we need to talk,” Ryan said, the fake sympathy evaporating. “We need to be practical.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean,” he said, shooting a quick look at Amber, “we need to settle the estate for everyone’s good.”

He stood, walked to his leather briefcase by the door, and brought it back to the table. The snap of the locks echoed in the quiet kitchen. He pulled out a thick folder and slid it across the table.

“What is this?”

“Mom’s estate file,” he said, his voice dropping into a serious tone. “Or rather, the lack of one. She died intestate, Dad. No will. Which means under the law the estate is split. You receive your preferential share, but the rest is divided among the children.”

My blood went cold.

“The house,” Amber said, right on cue. “This house is worth one‑point‑eight million, Dad. Maybe more in this market. That’s a lot of equity just sitting here.”

Ryan nodded. “Exactly. And honestly, you don’t need this big place anymore. It’s too much to maintain. The stairs, the yard. You’re sixty‑seven. You should be in a condo—something easier.”

He flipped the folder open. Real‑estate listings were paper‑clipped inside—one‑bedroom condos in New Westminster. Small places, cheap places.

“We’ve already talked to a realtor,” Ryan continued. “She can list it next week. We can probably close by February. You’d walk away with your share, buy something small, and still have money left over.”

“And what about your shares?” I asked quietly.

Ryan smiled. It didn’t reach his eyes.

“Well, obviously, Amber and I would split the remainder after your preferential portion. It’s only fair. We’re her children, too.”

“Fair,” I repeated.

“Dad, please,” Amber said, putting her hand on mine. Her nails were perfect, manicured. “Don’t make this hard. We’re all grieving, but we need to be smart. The market is hot right now. If we wait, we might lose value.”

She didn’t even pretend to cry.

“This house,” I said slowly, “is where we raised you. This is where your mother baked birthday cakes, where we had Christmas morning, where she taught you both to ride bikes in the driveway.”

“Exactly,” Ryan said. “It’s full of memories. But Dad—they’re just memories. You can’t live in memories. You need to live in reality. And reality is that this is a two‑point‑three‑million‑dollar asset that’s being wasted.”

Two‑point‑three. He had already had it appraised.

“I need time,” I said.

Ryan’s patience snapped. He wasn’t a forty‑two‑year‑old developer anymore; he was a spoiled child who wasn’t getting his way.

“You don’t need time. This isn’t complicated. Sign the listing agreement. Let us handle this. You’re grieving. You’re not thinking clearly.”

I stood up. Every one of my sixty‑seven years made my knees ache. But I felt something else—a cold, sharp anger I hadn’t felt since my last fire call.

“I want you to leave,” I said.

“Dad, don’t be reckless,” Ryan hissed, leaning forward. “This house is partly ours. You can’t just keep it. We have a legal right.”

“Get out of my house.”

“You’re going to regret this,” Amber said, her voice shaking. “We’re trying to help you.”

I walked to the door and opened it. The cold January air rushed in.

They left, but I heard Ryan on the phone before he even got to his car. He was calling his lawyer. I closed the door and stood there in the silence.

Then I remembered the safety‑deposit‑box key.

PART 2

Martha had given it to me two weeks before she died, her hands shaking so badly she could barely hold it. She had pressed it into my palm in the hospital.

“When I’m gone,” she whispered. “Go to the bank. Box 317. Don’t tell them. Don’t tell anyone. Just you.”

I hadn’t understood then. I did now.

I drove to the Royal Bank on Main Street—the same bank we had used for forty years. I showed them Martha’s death certificate and the key. The manager, a woman named Patricia who had known Martha, led me to the vault. She gave me privacy.

Inside Box 317 was a brown envelope and a USB drive. The envelope had my name written on it in Martha’s handwriting. I opened it with shaking hands. Inside was a letter—several pages—and something else: a document. The title made my heart stop.

Transfer of Land Title. Registered Owner: Walter James Morrison.

The date was three months ago. Martha had transferred the house into my name alone before she got too sick, before she lost her strength.

But it was the letter that broke me.

My dearest Walter, it began. If you are reading this, then I am gone. And I am so, so sorry. I am sorry that I had to keep secrets from you. I am sorry that our children have become the people they are. Most of all, I am sorry that you are alone now. But you are not defenseless. I made sure of that.

I know you are confused. I know Ryan and Amber came to you. I know they demanded the house. I knew they would because, my love, they have been demanding from us for years. And I have been too weak, too afraid to say no.

Ryan borrowed one‑hundred‑eighty thousand dollars from us—do you remember?—five years ago, for his investment opportunity. He promised to pay us back in six months. He never did. Every time I asked, he said the market was bad. The deal fell through. “Next quarter.” Always next quarter.

Amber took ninety‑five thousand for her lifestyle‑brand company—the one that failed in eight months. She never mentioned it again. She just moved on to the next thing. The next sponsor. The next filter.

I paid, Walter. I paid and I stayed quiet because I didn’t want to hurt you. I didn’t want you to see what they had become. But my silence was poison. It made them worse. It taught them that we were just a bank—just resources to be used.

When the doctor told me I had six months, maybe less, I knew what would happen. I knew they would descend on you. I knew they would try to take the house—this house, the one you built the back deck on, the one where we slow‑danced in the kitchen on our anniversary. So I did what I had to do. I transferred the house into your name alone. I made it ironclad. Community‑property rules don’t apply because it was my inheritance from my parents. Remember? The lawyer confirmed it. It’s yours—solely yours.

But there’s more. There’s something you need to see—something I recorded. It’s on the USB drive. I did it while you were at physical therapy. I’m sorry, my love. I’m sorry you have to see this, but you need to know the truth. You need to know who they really are. I love you, Walter. I have loved you since I was twenty‑two years old. You are the best man I have ever known. You deserve peace. You deserve to live the rest of your years without anyone trying to take what’s yours. So I built you a fortress. Use it. All my love forever, Martha.

I sat there in that small private room in the vault. I couldn’t breathe. I plugged the USB drive into my phone with the adapter I carried. One video file dated November ninth—three weeks before she died. I pressed play.

The video was shaky. Martha had propped her phone on the nightstand in our bedroom. She was in her chair—the one we had moved into the bedroom when the stairs got too hard. She looked so small, so tired. And then Ryan walked in.

“Mom, we need to talk.” His voice came through the speaker—not gentle, not concerned—impatient.

“About what, sweetheart?” Martha’s voice was weak.

“About Dad. About the house. About the future.”

“Ryan, I’m very tired. Can we—”

“No, we can’t do this later. You keep putting me off. Amber and I have been talking. We’re worried.”

“Worried about what?”

“About Dad managing everything when you’re gone. Mom, be realistic. He’s sixty‑seven. He’s had two knee surgeries. He can barely use email. How is he going to handle the estate? The house? The finances?”

“Your father is perfectly capable.”

“Is he, though? Mom, I love Dad, but he’s from a different generation. He doesn’t understand property values. He doesn’t understand investment. He’ll just sit in that house until he dies. And then what? The market could crash. We could lose hundreds of thousands.”

“Ryan, this is not the time.”

“When is the time, Mom?” His voice got louder. “When you’re gone? When it’s too late? I’m trying to protect this family. I’m trying to protect Dad, but I need your help. I need you to sign something.”

There was a rustling sound—papers.

“What is this?”

“It’s a transfer of beneficial interest. It puts the house into a trust. Amber and I are the trustees. We’ll manage it for Dad—make sure he’s taken care of—make sure the asset is protected.”

“This says the house goes to you and Amber—not to your father.”

“Well, yes, eventually. But Dad will have life interest. He can live there as long as he wants. We’re just making sure it’s protected for everyone.”

“Ryan, no. That house is your father’s home.”

“Mom, don’t be difficult. You’re sick. You’re not thinking clearly. This is what’s best. Trust me. I do this for a living.”

“I said no.”

There was a long silence. When Ryan spoke again, his voice was different—colder.

“Fine. Then I guess we do this the hard way. When you pass, there’s no will. House goes into probate. Amber and I will fight Dad for our share. It’ll take years. It’ll cost tens of thousands in legal fees. Is that what you want? You want Dad to spend his last years fighting us in court?”

“You wouldn’t.”

“Try me, Mom. You have two choices. You sign this now—we handle everything quietly—Dad never has to know—he gets to live in the house—and when he’s gone, Amber and I get what’s fair. Or you refuse and we make his life miserable. We tie up the estate. We contest everything. We’ll claim he manipulated you. We’ll claim diminished capacity. We’ll make him look incompetent.”

Martha was crying. I could hear it on the video.

“How did you become this?” she whispered.

“I became practical, Mom. I became realistic. Now sign the papers.”

“Get out.”

“What?”

“Get out of my room. Get out of my house.”

“Mom, you’re being—”

“Get out.” She was shouting now—weak but fierce. “Get out or I’ll call the police. I’ll tell them you’re trying to pressure me.”

There was silence. Then footsteps. The door slammed. The video continued for another minute. Martha sat there crying. Then she looked at the camera.

“Walter,” she said, looking right at me. “I’m so sorry you had to see this. But now you know. Now you understand. They’re gone, my love. The children we raised are gone. These people are strangers. Don’t give them anything. Don’t give them mercy. They wouldn’t show you. I love you. Be strong.”

The video ended. I sat in the vault. I don’t know how long. Patricia knocked softly.

“Mr. Morrison, are you all right?”

I wasn’t. But I would be.

PART 3

I drove home. I didn’t cry. I was past crying. I called the lawyer Martha had used. Her name was on the title‑transfer document: Sharon Chen. She agreed to see me that afternoon.

“Your wife was a very smart woman,” Sharon said after I showed her everything. “The house is yours completely. They have no claim. The transfer was done properly. She was of sound mind. We have the doctor’s assessment and the notary’s signature. It’s solid.”

“They’re going to fight,” I said.

“Let them,” Sharon replied. “They’ll lose.”

“And, Mr. Morrison—there’s something else. Your wife set up a trust for your grandchildren. Ryan’s two kids. Amber’s daughter. She put two‑hundred‑thousand into it for their education. But there’s a condition.”

“What condition?”

“Ryan and Amber can’t touch it. It goes directly to the kids when they turn eighteen. Your wife made sure of it. She told me she wanted to save something—something pure—for the next generation.”

Two‑hundred‑thousand. Money Martha had inherited from her parents. Money she had saved for decades. She had put it somewhere safe—somewhere Ryan and Amber couldn’t reach.

Three days later, Ryan’s lawyer sent a letter. They were contesting the title transfer—claiming Martha had been coerced, diminished capacity, undue influence. Sharon filed a response. She included the video. Ryan’s lawyer withdrew the case within forty‑eight hours.

But they didn’t stop.

Amber called me, crying. The tears sounded forced.

“Dad, please. I don’t have anywhere to live. My landlord raised my rent. I need help.”

“You have a career,” I said. “You have sponsors.”

“Those dried up. The algorithm changed. Dad, please. I’m your daughter.”

“My daughter wouldn’t have tried to take my home.”

I ended the call.

Ryan showed up at the house late one night, pounding on the door.

“You can’t do this. That house should be mine.”

I called the police. They issued a warning. I changed the locks. I put up a security camera.

And then I did what Martha had wanted me to do. I lived.

I sold the house—not to put a cent into Ryan and Amber’s pockets, but because Martha was right. It was too big. Too many stairs. Too many memories that hurt now. I sold it for two‑point‑four million. I bought a small condo in Kitsilano—two bedrooms, a balcony with a view of the ocean, everything on one floor. The rest of the money I placed into the trust for the grandchildren—Martha’s trust. I added another five‑hundred‑thousand. The lawyer made sure Ryan and Amber couldn’t touch it, couldn’t borrow against it, couldn’t manipulate the kids into signing it over.

Those kids—they’re nine, seven, and five now. They don’t know what their parents tried to do. Someday they will, but for now they have a future. They have education funds. They have something their parents can’t ruin.

I see them sometimes. Ryan drops them off for visits now—not because he’s sorry, but because his wife insisted. She saw the video. She was horrified. She threatened to leave him if he didn’t make peace. The visits are awkward, tense. But the kids don’t know that. They just know Grandpa has cookies and takes them to the aquarium.

Ryan and Amber are different now. Quieter. Amber got a real job at a fitness studio, teaching yoga. Not glamorous, but honest work. Ryan sold his condo in Toronto—downsized. The developments aren’t going as well as he claimed.

I don’t take pleasure in that. I don’t feel victorious. I just feel tired and sad. Sad that it came to this. Sad that my children became people I don’t recognize.

But I also feel something else—something Martha gave me in her last act of love. I feel free.

PART 4

I go to the cemetery every Sunday. I bring flowers—white roses, her favorite. I sit on the bench next to her grave and I talk to her. I tell her about the grandkids, about the condo, about the ocean view.

“You were right,” I tell her, about everything. “You were always right.”

The wind blows in from the water—cold and clean—and I can almost hear her voice, almost feel her hand in mine.

You’re free now, Walter, she would say. Live.

So I do. I wake up in the morning in my small, bright condo. I make coffee. I watch the sunrise over the water. I call my old buddies from the fire station. We meet for breakfast. We tell old stories.

I’m not much of a father anymore—not really. That relationship died when my children chose money over love. But I’m still a grandfather. I’m still Martha’s husband. Even in death, I’m still Walter Morrison. And for the first time in years, that’s enough.

This isn’t about anger. It isn’t about revenge. It’s about boundaries. Love and trust are not the same as enabling bad behavior. Sometimes the people we love most become strangers we don’t recognize. Real strength isn’t about being the biggest or the loudest—it’s about having the courage to say no, to set limits, to protect yourself from anyone who would use your love against you.

Martha’s final act wasn’t just about saving the house. It was about saving me—about giving me permission to live without guilt, without obligation to people who had stopped acting like family a long time ago. It’s a reminder that it’s never too late to start over. Peace isn’t found in wealth or status or perfect children. It’s found in knowing you did the right thing. In honoring the people who truly loved you. In refusing to be a victim.

What would you have done in my place? Would you have fought? Would you have given in? Would you have found the strength to walk away?

Tell me your thoughts—kindly and respectfully.