The armory at Camp Liberty sounded like a hundred small clocks—bolts easing forward, springs settling, metal catching a thin smear of oil and then going quiet. Afternoon light fell in a slant across racks of rifles and pelican cases; dust hung in the beam like static.

Staff Sergeant Luna Valdez—callsign Ghost—sat in the far corner on a rubber mat, the Barrett M82A1 stretched along her forearms like a length of dark sky. She moved through her ritual the way surgeons scrub: deliberate, sequenced, nothing wasted. Receiver open. Bolt carrier checked. Lugs inspected. Chamber polished until her reflection returned in a faint, warped oval.

Most days, officers flowed past her without slowing. A sniper is loud at distance and invisible up close. Today, a pair of dress shoes clicked to a stop.

“Carry on, soldier,” said a familiar voice. General William Matthews, weekly inspection, aide in tow.

Luna glanced up, nodded. “Roger, sir.”

He would’ve kept walking if the light hadn’t caught a sliver of enamel on her blouse—one of those small, forgettable rectangles no one notices until they do. He leaned. Read. Blinked.

3,200‑METER CONFIRMED.

He read it again as if the numbers might rearrange themselves into something reasonable.

“Soldier,” he said carefully, “that’s not possible. No one makes a shot at that distance.”

Luna set the bolt on a blue cloth. No defensiveness, no performance—just the calm of a person who speaks precisely for a living.

“Sir, the engagement was recorded by mission command and verified by multiple observers. Documentation exists at a classification level above this facility.”

Lieutenant Colonel Harrison, the aide, was already tapping a tablet. “Sir… her open record shows Sniper School top marks, advanced long‑range courses, reconnaissance certifications I don’t recognize, attachments to the 75th Ranger Regiment, and—” He hesitated. “And entries redacted under special access.”

The general’s gaze slid to the Barrett. “Valdez, explain to me how anyone makes 3,200.”

“Understanding, patience, and environment,” she said. “Multiple wind calls along the flight path, air density and temperature gradients, barometric pressure, spin drift, Coriolis. Precise range. Stable position. And time. A lot of time.”

“How much time?”

“Four hours of prep for one trigger press.”

He studied her for a moment—late twenties, calm eyes, sleeves perfectly rolled. Nothing theatrical. Nothing to sell. Just competence.

“I want to see a demonstration.”

“Sir, extreme distances require special ranges and approvals. Your long bay tops out at twelve hundred.”

“Then we start there,” Matthews said. “Harrison—range control, safety, whatever she needs.”

Two days later, the wind at the extended bay barely bothered the grass. The sky had that dry Texas clarity that turns edges crisp. Targets shimmered at 1,200 meters like stamps on a bright envelope.

Luna arrived early and made the dirt her desk. Weather meter. Kestrel. Laser rangefinder. A small ballistic computer with a cracked corner. She moved between instruments, writing the day into numbers.

“Talk me through,” Matthews said, binoculars up.

“Wind at muzzle, wind at mid‑path, wind at target,” she said, watching a strip of surveyor’s tape thirty feet out. “Temp, pressure, density altitude. Flight time and drop. Adjusting for spin drift right, three‑tenths mil. Holding a whisper of left for the quartering breeze.”

She settled in behind the Barrett, body a straight line, cheek weld light as breath. The range went very quiet in that way places do when everyone is waiting for one sound.

The rifle spoke. The earth pushed back into her shoulder. A heartbeat later the spotter called, “Impact, center.”

Matthews didn’t answer; he was already looking through glass. The hole in the target sat where a coin could cover it.

“At twelve hundred,” he said finally. “And you’re telling me you’ve done nearly triple.”

“Not today,” she said. “On a mountain. With elevation. With time. With a still target. With conditions that lined up like they’d been ordered to.” She eased the rifle safe and sat up. “Extreme shots aren’t stunts. They’re logistics.”

The general lowered his binoculars. Something in his expression had shifted from disbelief to study.

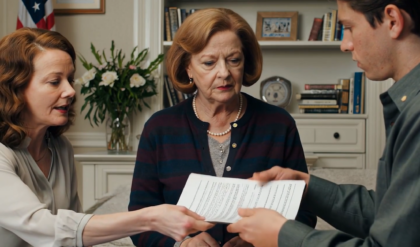

Bureaucracy moves slow until the right signature learns why it shouldn’t. A week later, Matthews sat in a windowless room with a burn bag, a carafe of coffee, and a stack of folders whose covers carried more stamps than titles.

General Patricia Stone briefed without ornament. “Staff Sergeant Valdez is a specialized capability. She is tasked strategically, not tactically. You will not see her in unit highlight reels. You will feel her in outcome reports.”

Matthews flipped a page and found a line that wasn’t a line so much as a hinge: HOSTAGE INCIDENT—MOUNTAINOUS TERRAIN—CONVENTIONAL ASSAULT RISK UNSUPPORTED—SOLUTION: ELR PRECISION.

He imagined four hours of stillness for four seconds of flight that changed the shape of a night.

“Why Camp Liberty?” he asked.

“Because capability isn’t a museum piece,” Stone said. “It’s readiness. She cleans because she might need to go.”

Back at the armory, life returned to its clockwork. Boots. Solvents. Quiet talk that died as soon as it was born. Luna’s mat waited in the corner. The Barrett rested nose‑forward in its case, oiled and patient.

Matthews paused at the threshold, then walked the long way around the racks to where she sat.

“Staff Sergeant,” he said, softer than before.

“Sir.”

He nodded at the small enamel rectangle. “Badges tell stories. Some louder than others.”

“Yes, sir.”

“I won’t ask you to tell me that story,” he said. “But I’ll make sure the right people know it’s there.”

“Yes, sir.”

He looked at the rifle, then the soldier. “People think precision is about the trigger,” he said.

“It’s about everything before it,” she answered.

He almost smiled. “Carry on.”

Six months later, a report crossed Matthews’s desk with more white space than text. The summary paragraph was a haiku of facts: complex terrain, limited options, precision solution, all lives recovered. He read it twice and closed the folder.

Somewhere, a soldier who cleaned her weapon like a metronome had waited out four hours of wind and doubt so that one moment could land exactly where it needed to. No applause. No headlines. Just a line in a quiet file and a small badge that people rarely notice until they can’t look away.

If you’ve ever dismissed the person working in the corner, remember: exceptional capability often hides where attention doesn’t. The difference between routine and remarkable is usually preparation you never saw.

Luna Valdez didn’t chase the impossible. She prepared for it—until it looked like skill, and then like standard, and then like the reason a mission ended the right way.

And most days, she still walked past the noise, rolled out her mat, and made the metal shine.