The camera shakes once—just enough to blur the tassels and the light. In the frame, a Texas gymnasium blooms with noise: metal bleachers, paper programs, a sea of mortarboards. Celeste and Steven Beard sit together in the stands, clapping as their twin daughters, Jennifer and Kristina, cross the stage. A row ahead, a woman sits by herself, hands meeting in practiced applause. Her name is Tracey Tarlton. She looks like support.

From the outside, it’s a family milestone in Austin: twins in matching gowns; a mother with bright eyes; a stepfather with proud shoulders; a friend from the bookstore clapping in time. But the footage hides a secret the twins don’t know yet—that months earlier, Tracey walked out of a psychiatric facility and, in the quiet corners of Austin, began meeting Celeste in secret to plan a violent act that would send two teenagers running for their lives.

“Not enough locks,” one of the girls would say later. “We were scared to death.”

The story begins earlier. In 1993, the twins are thirteen. Kristina lives with Celeste and her new husband, Steven, in Austin. Jennifer lives a thousand miles away with their father, Craig, in Washington State. The divorce carved the girls in half—two best friends assigned to different skies.

“I missed her a lot,” one says. “We were built‑in friends.”

“It’s always been nice to have someone who knows exactly what I’m going through,” the other adds. “It was hard not having my other half.”

Three years pass. It’s July 1996 when they finally plan a reunion—grandparents’ house in California, a summer reset. They haven’t seen each other in more than two years. The laughter when they do meet is the kind that folds you over.

Then the calls to Washington go unanswered. One day. Two. The news arrives like a dropped plate: their father has been found dead in his home, a letter left behind. He had been struggling quietly for years. Shock wraps the twins like cold water.

What was supposed to be a two‑week visit becomes a permanent reroute. Jennifer moves to Austin to live with Kristina, their mother Celeste, and Steven Beard. The adjustment is a braid of grief and surprise. Steven—retired TV executive, older, soft‑spoken—meets her with breakfasts and attention. On Sundays, he and Jennifer sit in a booth, the ritual landing like a lifeline. It helps.

From the outside, the blended family looks settled. The girls begin senior year together. Steven formally adopts them and gives each a family ring. The gesture anchors something. “I felt connected to him,” one says. “He always wore his.”

October 2, 1999—2:30 a.m. Jennifer is at her boyfriend’s place. Kristina sleeps at home. The bedroom door bursts open, light chasing the dark. Celeste barrels in, voice high: “Someone’s at the door.” Sirens. Flashing lights. Kristina grabs the phone and calls 911, breathless. The dispatchers tell her the lights outside belong to police. Moments earlier, a separate 911 call came from inside the house.

Kristina opens the front door. Officers ask for her dad. Upstairs, paramedics work over Steven. Blood. Urgency. A shotgun shell near the bed—evidence on a bedroom floor.

“He was shot?” Kristina asks. Yes.

Steven is airlifted to the hospital. The house becomes a crime scene—side door unlocked, footprints of intention leading to a room where an old man slept. Investigators swab, photograph, list. They collect DNA from everyone who might have touched anything: the twins and their mother.

As the girls step outside, Celeste leans in, whispering into Kristina’s ear: “If the police ask who might’ve done this, don’t mention Tracey’s name.” The instruction lands wrong. Do not say the name of the woman who’s been orbiting their mother for months. A friend. Graduation attendee. Bookstore manager.

“Why would she say that?” the girls wonder.

At the hospital, a detective asks Kristina who she thinks shot her father. “I’m not supposed to say the name,” she answers, shaking, “but Tracey Tarlton.”

Tracey becomes a suspect. Investigators follow the most stubborn facts: a 20‑gauge shell at the scene; the bookstore manager with a new closeness to Celeste; the psychiatric facility where the two women met and started spending time. A search warrant for Tracey’s house. A knock on her door.

“Do you own a shotgun?”

“Yes.”

“May we see it?”

A Franchi 20‑gauge—her name etched into the metal. The weapon goes into an evidence bag. Lab work follows. Days later: a match. The shot that tore into Steven Beard came from Tracey’s gun.

October 8, 1999—five days after the shooting—Tracey is arrested and charged with attempted murder. She refuses to explain why. Detectives feel a gravity they can’t see yet. It doesn’t feel like a solo act.

While law enforcement waits on words Tracey won’t give, Steven fights. Months pass in the dull fluorescent light of a hospital, the twins at his side. Then the line flattens. He dies from complications tied to the shooting. Grief arrives again, again.

The girls move through funeral arrangements with their mother. A casket to choose. A loss to name. In the middle of tears, Celeste does something that freezes the air: she buys two pink caskets for her eighteen‑year‑old daughters.

“I’m going to get these for you,” she says.

A chill swings through the room. “Do I need this soon?” one girl wonders. “Am I going in here?”

Austin media begin to circle. The story hits papers and TV. Without a clear motive, the case stalls. At home, the twins watch their mother become manic and loud, laughing in rooms that shouldn’t hold laughter.

Then February 16, 2000. Nobody is ready for what happens in a quiet house with two teenagers. Celeste says, “Why don’t we all kill ourselves?” and pulls a knife. She lunges and plunges it into her own leg. Blood floods. The twins call 911, pleading. Paramedics arrive and take their mother to the hospital.

From there, the phone calls come—Celeste’s voice swinging between screams and sweet, normal and cruel. Kristina gets an idea. She records the conversations—not to trap her mother, she tells herself, but to play them back so Celeste can hear how she sounds.

Then, on one of those tapes, a sentence cracks the case open.

“I hired somebody to kill Tracey,” Celeste says.

The words still the room. The twins hear danger more clearly than they ever have. The pink caskets. The laughter at strange times. The old man in the bed. The new plan to remove the only witness who can put Celeste in a courtroom.

The girls go into hiding. They pull cash, check into motels, use no cards. “We stayed with cash,” Jennifer says. “We thought we weren’t coming home.” They obtain a family‑violence protective order against their mother. The tapes go to police.

Tracey sits in jail, silent, awaiting trial on the shooting. She says nothing about Celeste until March 2002, when she reads in the paper that the twins got a protective order. Something shifts. She calls investigators and breaks her silence. Celeste had a plan, she says. Celeste called the play.

With Tracey’s statement and the recordings, the pieces finally link. On March 28, 2002, Celeste is arrested for capital murder. The twins feel a thin new thing: a chance at safety. It will take a jury to harden it into fact.

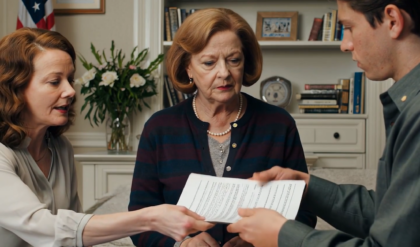

February 3, 2003—trial begins. The twins will have to sit in the same room as their mother. They will have to point at the truth and keep their hands from shaking.

“I didn’t want to be in the same room,” one says. “But I wanted Steve to get justice.”

In court, the sisters describe a childhood under a storm cloud—mood swings like whiplash; threats; phone calls that cut and never stopped cutting. They testify that when Celeste married Steven Beard—sixty‑nine, retired, a millionaire—she told them it was for money, not love. If Steven died, she’d get everything. “Why won’t he die already?” she had said more than once.

Financial records show that within six months of marrying, Celeste spent over $500,000—clothes, jewelry, art. The twins tell the jury they saw Celeste slip sleeping pills into Steven’s food and slip out after he slept. They describe a breakdown in February 1999 when Celeste pointed a gun at her own head and threatened Kristina, then was committed to St. David’s Psychiatric Hospital—where she met Tracey.

Tracey takes the stand. She describes the relationship—Celeste’s attention, the intimacy, the story of an “abusive” husband that wasn’t true. She says Celeste proposed a solution.

“He’s an old man,” Celeste had said. “He’s going to die soon—but not soon enough.”

Tracey recounts the walk‑through: where to park, which door to use, how to climb the stairs, how to approach the bedroom. “I saw him,” she says. “I held up the shotgun and I shot him. Once.”

In the gallery, Celeste shakes her head and even laughs at times. Her face changes when her daughters take the stand again—not just to talk but to play the tapes. The courtroom listens to a mother’s voice swing from honey to blade. “It was difficult to think any mother would talk to a child that way,” someone says later.

The trial runs for weeks. On March 19, 2003, after three days of deliberation, the jury returns. The judge asks anyone likely to erupt to leave the room. The foreperson reads.

“State versus Celeste Beard Johnson. Verdict—capital murder. We, the jury, find the defendant guilty of the offense of capital murder.”

The twins feel a flood—grief, relief, the ache of what a mother is supposed to be. The sentence follows: two consecutive forty‑year prison terms. Parole eligibility won’t come until she’s seventy‑nine.

After court, Tracey asks to see the twins. She apologizes for killing Steven. She says she’s sorry. “I could relate,” a daughter says quietly. “She was a victim here too.” Forgiveness doesn’t undo the dead. It does loosen the knot enough to breathe.

Twenty years pass. The sisters’ bond is the thread that didn’t break. Jennifer is forty‑two now, steady work and steady care for herself. Kristina married and has two kids. “I’m going to be the mom I wanted,” she says. “They get to live the life I wished I had.” The twins visit when they can. They are, for each other, exactly what they were at thirteen in two different states: witness and home.

Celeste never expected her downfall would come from her daughters—the two people she had counted on to keep her secrets or absorb her versions of love. The twins never expected that survival would look like telling a room full of strangers how a mother can starve a house of safety.

In Austin, time keeps moving—church bells, summer heat, the long shadow of a case that once pulled a city into its questions. The proof the twins offered—their tapes, their testimony, their refusal to look away—became a door other people could walk through. And on the other side, the sisters found what they were promised all along and had to retrieve themselves: a life worth living.